Henry VI and the Art of Political Spin

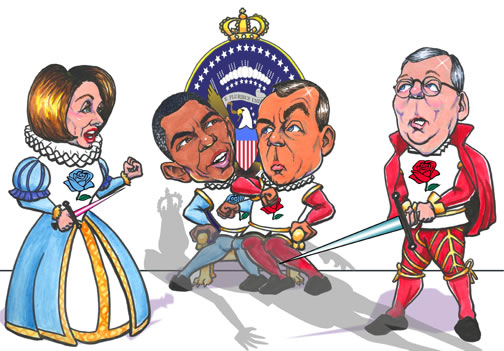

America Is Witnessing Its Own Version

of the War of the Roses

In the recent round of intense bickering between the Democrats and Republicans over budget cuts versus tax increases vis-à-vis the national debt, President Barack Obama invoked the name of one of his predecessors as he dug in against his opponents. That name was Ronald Reagan.

It's almost too easy to draw parallels between the War of the Roses as William Shakespeare presented it in his three Henry VI plays and the War of the PAC Animals we're witnessing today. Shakespeare depicted how the red-rose Lancastrians and white-rose Yorkists contended over the succession to the English crown. Today, we are watching the red-elephant Republicans and blue-donkey Democrats contend over the succession of the U.S. presidency.

In both, you have lawmakers (noble men and women in pedigree if not in behavior) publicly sniping at each other. In both, you have government authorities charged with working together for the public's best interests intentionally perpetrating failed outcomes in order to create blame for their opponents. In both, you have these same authorities spending more energy scheming to bring dishonor on their opposition than governing. In both, you have a grassroots uprising (fomented by some of the above-mentioned lords) intent on getting more for themselves and their families and fellows. You have factions changing allegiances, from king to king on the one hand and from policy to an opposite policy on the other hand, prompted by the only ideal they adhere to: political expedience. You even have women perceived as she-wolves in both conflicts. These two color-coded wars also share in inflated egos, assertions of divine order, a government tottering on bankruptcy, and the common people suffering most.

These parallels probably emerge as more a matter of history repeating itself than Shakespearean foresight. Rather than the historical coincidences between the 15th century fight over the English throne and the 21st century fight over the Oval Office desk, I'm most intrigued by Shakespeare's keen insights into human nature that is playing out today in the same manner as he depicted in his plays: In particular, how today's politicians put political spin ahead of facts, rewrite history, and pretend to be oblivious to omnipresent figures hovering over the scene.

To understand the context in the Henry VI plays, here is a brief primer. The English monarch is a hereditary succession, passing first to the eldest male offspring, then to the eldest living son of that eldest male offspring before moving to the next eldest son, and so forth until there are no more direct male offsprings, at which point it jumps over to the eldest female offspring. When the ruling monarch has no children, as was the case with Elizabeth I, some cousin can be found to continue the line.

This standard was also used to justify usurpations. The War of the Roses came about because Edward III had nine children who lived to adulthood and had children. His eldest son, the Black Prince, died before Edward III did, so the crown passed next to the Black Prince's young son, Richard II. Richard “abdicated” to another of Edward III's grandsons, Bolingbroke, the Duke of Lancaster, who became Henry IV. The crown passed next to his eldest son, Henry V, who then bequeathed it to his only son, Henry VI. Thanks to the last Henry's weakness (heck, he was only nine months old when he was crowned, and he didn't mature much more even as he became an adult), other descendants of Edward III began stirring for power, most notably Richard, Duke of York, who traced his lineage to two of Edward III's offspring, one of whom was older than Bolingbroke's father, John of Gaunt.

York's argument, repeatedly asserted by him and his followers in Shakespeare's plays, is that Bolingbroke usurped the crown, so the Lancaster line's claim to the throne, i.e., Henry VI, not only has no authority but is treasonous. When Henry VI tries to parse the fact by telling York “Henry the Fourth by conquest got the crown,” York replies “'Twas by rebellion against his king,” at which point Henry VI falters, saying in an aside: “I know not what to say, my title's weak” (Henry VI, Part 3, I.1.133). Here York conveniently forgets that his father was executed for treason against Henry V, and it was Henry VI who reinstated the family's title.

There's a bigger problem with the Yorkist argument, however: Henry V himself. Even in Shakespeare's time, Henry V was considered England's greatest king, the monarch who conquered France and brought unequalled prosperity and pride to his people (Shakespeare himself was to depict Henry V in a play several years later). By claiming Henry IV's line as illegal, York is by implication saying Henry V was an illegitimate king. Ah, but the White Rosers aren't about to go there. So, the Yorkists conveniently leave the middle Henry out of their arguments, and any time Henry VI or other Lancastrians point this out, the Yorkists feint to an unrelated fact.

When Henry says “I am the son of Henry the Fifth, who made…the French to stoop,” Warwick quickly rebuts, “Talk not of France, sith thou hast lost it all” (Henry VI, Part 3, I.1.108). Warwick uses the same fallback later in the play when he and Lancaster supporter Oxford are stating their cases in seeking support from France's King Lewis. Oxford starts with John of Gaunt and traces the line through “that wise prince, Henry the Fifth, who by his prowess conquered all France: From these our Henry lineally descends.” “Oxford,” counters Warwick, “how haps it, in this smooth discourse, you told not how Henry the Sixth hath lost all that which Henry Fifth had gotten?” (Henry VI, Part 3, 3.3.86).

Talk about spin. Shakespeare's Warwick refined this art 400 years before it became common practice in America's political debate. Rather than lose the debate on Henry V's (and thus Henry VI's) ancestry, he adroitly changes the terms of the debate.

Aside from this depiction of political spin, the specter of the great King Henry V hanging over the Yorks is not much different from the specter of Reagan hanging over the Democrats. When he ruled, Reagan faced loud opposition, but now, a generation later, he has risen to such a stature of hero worship that the Democrats don't dare denigrate him. Indeed, the Democrat Obama invoked Reagan's name to advance his own cause. Similarly, the Republicans are trying to dismantle many of the policies Franklin D. Roosevelt put in place while trying not to deny his popular legacy.

Another parallel: Henry VI is quick to point out that Henry V was his father, but he abandons his predecessors' policies at every turn. So, too, have today's Republicans, claiming to be carrying on Reagan's legacy, almost wholly abandoned the pragmatist politics Reagan endorsed. In Shakespeare's plays, it's the Yorkists who endorse Henry V's policies, and today it's Obama who quotes Reagan in advancing his economic platform.

I'm not sure there's a lesson in all this, except that it is another of many examples of Shakespeare's amazing insight into human nature across the ages. But there is hope. For all the Yorks' and Lancasters' hereditary claims, the throne was eventually won, and a lasting dynasty created, by the Earl of Richmond (Henry VII), whose tenuous line to Edward III ran through a bastard. That's another universal theme: Good governance and effective leadership are no more hereditary than they are entitled.

Of course, Henry VII's ascent comes at the end of Shakespeare's subsequent play. That should be a caution to everybody, Democrat and Republican, tea-drinking and independent, to remember that Shakespeare's Red vs. White Roses war culminated in the bloody titular tyrant of Richard III. Let's hope our parallel Red versus Blue contention skips that play.

Eric Minton

September 19, 2011

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom