Where There's a Will

Where There's a Will

Shakespeareances Through the American Way

The Shakespeare Canon Project crisscrossed North America to see all 42 Shakespeare-penned plays at 42 different theaters in 2018—a year the 454-year-old playwright presciently depicted. Meanwhile, back home, a comic subplot twists into a mysterious drama.

Seeing every play in William Shakespeare's canon performed on stage is a bucket-list achievement for his fans.

Seeing every Shakespeare play in one year is a stunt.

Seeing all 42 Shakespeare plays each in a different theater in one year, that's insane, as more than one actor told me.

It's also revealing. What develops is Shakespeare's snapshot of America in 2018, his plays lining up with the year's headlines as Shakespeare himself embraces what it means to be American. Meanwhile, chaos comes into my own life during the journey. Seven plays into the quest, I take my wife to the emergency room during a snowstorm and soon discover that a more serious storm has been brewing inside her head.

Below is the real-time journal of this enterprise.

THE ITINERARY

Shakespeareances Announces Canon Project

Twelfth Night, or What You Will

Fiasco Theater

New York, New York, January 5

Hamlet

Shakespeare Miami

Miami, Florida, January 13

Richard II

American Shakespeare Center

Staunton, Virginia, January 27

Cymbeline (aka Imogen)

Pointless Theatre

Washington, D.C., February 10

Coriolanus

Brave Spirits Theatre

Alexandria, Virginia, February 10

Romeo and Juliet

Valley Shakespeare Festival

Shelton, Connecticut, February 15

The Merchant of Venice

Children's Shakespeare Theatre

Palisades, New York, March 3

Henry IV, Part 1

Southwest Shakespeare Company

Mesa, Arizona, March 29

Sir Thomas More (excerpt)

Night Shift's Drunken Shakespeare

New York City, April 16

Othello

Baltimore Shakespeare Factory

Baltimore, Maryland, April 21

Macbeth

Chicago Shakespeare Theater at Navy Pier

Chicago, Illinois, May 30

Much Ado About Nothing

Pigeon Creek Shakespeare Company

The Rose, Blue Lake Arts Camp, Michigan, June 2

Timon of Athens

Shakespeare in the Ruins

Winnipeg, Manitoba, June 5

The Comedy of Errors

Kentucky Shakespeare

Louisville, Kentucky, June 9

Pericles, Prince of Tyre

Sweet Tea Shakespeare

Fayetteville, North Carolina, June 15

King Lear

Shakespeare in the Vines

Temecula, California, June 22

The Winter's Tale

Shakespeare by the Sea

San Pedro, California, June 23

The Tempest

The Old Globe

San Diego, California, June 26

The Two Noble Kinsmen

Kingsmen Shakespeare Company

Thousand Oaks, California, June 30

The Merry Wives of Windsor

Fairbanks Shakespeare Theatre

Fairbanks, Alaska, Juy 7

Henry VI, Part 1

Utah Shakespeare Festival

Cedar City, Utah, July 10

Henry VI, Part 3

Taffety Punk Theatre Company

Folger Theatre, Washington, D.C., July 16

Antony and Cleopatra

Palm Beach Shakespeare Festival

Jupiter, Florida, July 19

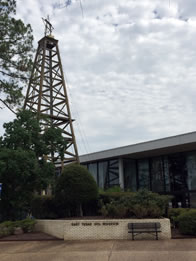

King John

Texas Shakespeare Festival

Kilgore, Texas, July 21

Titus Andronicus

Shakespeare on the Saskatchewan

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, July 25

As You Like It

Shakespeare by the Sea

St. John's, Newfoundland, July 28

All's Well That Ends Well

Ohio Shakespeare Festival

Akron, Ohio, August 3

Edward III

Colorado Shakespeare Festival

Boulder, Colorado, August 5

Arden of Faversham

Shakespeare at Winedale

Rount Top, Texas, August 10

Measure for Measure

American Players Theatre

Spring Green, Wisconsin, August 18

The Taming of the Shrew

First Folio Theatre

Oak Brook, Illinois, August 19

Henry VI, Part 2

National Asian American Theatre Company

New York, New York, August 25

Troilus and Cressida

Long Beach Shakespeare Company

Long Beach, California,

September 2

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Independent Shakespeare Company

Los Angeles, California,

September 2

Julius Caesar

Strratford Festival

Stratford, Ontario, September 12

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

Tennessee Shakespeare Company

Memphis, Tennessee,

September 22

Love's Labour's Lost

Oregon Shakespeare Festival

Ashland, Oregon, October 2

Richard III

upstart crow collective

Seattle, Washington, October 6

Henry VIII

Prenzie Players

Davenport, Iowa, October 12

Henry IV, Part 2

Atlanta Shakespeare Tavern

Atlanta, Georgia, October 20

The Spanish Tragedy

Hudson Shakespeare Company

Public Libraries in Montclair, Westfield, and South River, New Jersey, October

23-25

Friday, January 5—The Well-Worn Path

to Undiscovered Country

We're driving up the Jersey Turnpike. This used to be home for me. My father was a U.S. Air Force chaplain, and he was stationed at McGuire Air Force Base in central New Jersey during my high school years. My childhood finished up here.

One among the many times I've traversed this highway was on a bus. The Northern Burlington County Regional High School Drama Club was taking a field trip to the American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut, to see a production of William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night. My Shakespeareances started here.

I was not a member of the Drama Club—I had already launched my journalism career as editor of the high school newspaper and covering sports for the Bordentown Register-News. I was on this trip because my best friend, Mike, was the only guy going, and he wanted a bit of brotherhood for the road. I hated reading Julius Caesar in sophomore English, my only previous encounter with Shakespeare, and I had no knowledge of Twelfth Night. But hanging with Mike and a couple dozen girls seemed like a nice way to spend a Saturday. However, it was not Mike nor Sharon (a girl on the trip I would subsequently fall madly in love with) and not even Shakespeare that turned this into an extraordinary day.

It was Herman Munster. I didn't know it at the time, but at the other end of the bus trip was Fred Gwynne playing Sir Toby Belch in Shakespeare's play. I was a huge Munsters fan, and to see Herman right there, in person, and being more genially funny than he was on the TV show was a blow-away moment for this 16-year-old. "These clothes are good enough to drink in—and so be these boots, too," he said, pulling yet another hidden flask out of his boot as Maria stalked him around the stage intercepting his other drinking vessels in the play's third scene.

That was my first live production of a Shakespeare play. I've seen 493 since, including every play in the canon (the 36 First Folio plays plus Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen). Now I'm setting out to see all 42 Shakespeare plays—the 38 of the traditional canon plus four plays of the "Shakespeare Apocrypha" in which scholarship has found his hand—in 42 different theaters across North America in this single year, 2018.

Poetic justice is served by a production of Twelfth Night leading off my campaign, but that was not intentional. This Shakespeare Canon Project is built around opportunity more than sentimentalism, piecing together a matrix of what I can see when and where, and how by whom. Even as I start this journey, I lack assurance that five of the plays will be staged, though many theaters have yet to announce their summer or fall seasons. Henry VIII is rarely done, the Part Twos of two other Henry plays have empty lines on my matrix as does another obscure piece, Cymbeline. One apocryphal play is lacking, The Spanish Tragedy. The surprising absence in announced playbills is The Two Gentlemen of Verona, a play frequently staged the past few years. Perhaps it has ridden out its cyclic wave of popularity as King John and Love's Labour's Lost ride in on their waves in 2018. Or perhaps the socially and politically omnipresent #MeToo movement's focus on sexual assault and harassment might be scaring theaters away from The Two Gentlemen of Verona, a slapstick comedy with stalking and rape as plot points.

That, however, is the exact kind of context, specific to 2018 (as opposed to, say, 1600, the midpoint of Shakespeare's playwriting career), that this journey intends to engage through Shakespeare's plays. His works also titillate personal relevancy, pertinent especially at this particular stage of my life. I turn 60 this year; I'm entering Jacques' sixth age of man's mortality, shifting "into the lean and slippered pantaloon." I'm the father of two sons. The eldest is a Shakespearean actor in New York already playing old geezer roles. The youngest just announced his impending marriage in the fall in Seattle. They are the products of my first marriage. My second marriage, to a now-retired Air Force officer, Sarah, will enter its 26th year of bliss thiss summer.

And here I am reflecting on my first Twelfth Night 44 years ago that set me on the way to where I am today, heading up the Jersey Turnpike once again to see Twelfth Night—the 27th time I will have seen that play.

Sentiment of another kind made this Twelfth Night my first pick for this yearlong excursion through America's Shakespearean landscape. This time I know what's at the other end of the road: Fiasco.

Twelfth Night, Fiasco Theater

Classic Stage Company, New York, New York, January 5

Approaching New York City—by plane, by train, or, as now, by car—always thrills me. During the day, you're navigating a cat's cradle of roads while speed-reading highway signs when skyscrapers suddenly sprout up from the horizon beyond the Jersey swamps. At night, New York emerges from the distance as a galaxy of lights, the red rocket-topped Empire State Building piercing through the middle of it all. I love New York City. I love its vibrancy, its attitude, its pace, its people—salt-of-the-earth kind of people, brusque as they go about their business but courteous to the core.

Classic Stage Company's entrance, 136 E 13th St., New York City, where Fiasco Theater is staging Shakespeare's Twelfth Night. Photo by Eric Minton.

New York is, of course, one of the world's capitals for theater. We come here a lot, but that's as much due to supply as quality. Broadway is famous, but we see Shakespeare as good or better in both talent and execution in regional theater or "the provinces" (which I'm here defining as anywhere outside a nonmajor metropolitan center; in America, "the provinces" is generally defined as anywhere but New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles; in New York it is defined as anywhere but New York). When we come to New York to see Shakespeare, it's usually at a theater (or even a space, like a parking lot) that is designated with one or more tags of Off before Broadway, or the production is a loaner from the world's other major capital for theater, London.

As inviting as we find this city, it is cold on this night: 15 degrees, snow piled along the sidewalks, and slush in the streets. Turn a corner and the temperature drops to well below zero as an arctic gust blasts your skin, even that covered in clothing. This is the day after a "bomb cyclone" hit the East Coast (meteorologists seem to come up with new names for "storm" every year), and even New Yorkers seem daunted by the bitter cold: the streets are relatively empty. We trudge our way to Classic Stage Theater on East 13th Street near Union Square and walk in to warmth: the lobby coffee shop is packed with patrons distributed evenly across four generations. The doors open to the 200-seat deep-thrust theater. Inside, all is brick walls, wood-board floor, and ropes under a barn ceiling's light grid. Rustic trunks, furniture, and a lobster trap occupy the center of the stage. At the back are various instruments, and a ship's wheel inside a fishnet attached to an upright piano.

Typical of Fiasco Theater, a company of young actors who delve deep into Shakespeare's texts to create vibrant theater using as few as six cast members. This is the fifth production by Fiasco Theater we've seen: Measure for Measure at New York's New Victory Theater (Off-Broadway, of course), The Two Gentlemen of Verona and Cymbeline at the Folger Theater in Washington, D.C., and Stephen Sondheim's Into the Woods at Washington's Kennedy Center. The company's breakthrough production of Cymbeline, featuring a multitasking trunk, remains one of my favorite productions of all time. For Twelfth Night, the company expands to a cast of 10, which, with David Samuel doubling as Antonio and Fabian, still requires textual massaging: Maria (Tina Chilip) gets additional duty in the play's last scene.

As I anticipated, Fiasco's Twelfth Night is not only worth the four-hour drive to New York (back home again in the morning), it is worth the frostbite. The actors stage a laughter-full play and create a community experience by interacting with the audience before and during the play. Feste, played by co-director Ben Steinfeld (co-founder of Fiasco along with Noah Brody and Jessie Austrian), is alone worth the effort.

Nevertheless, people wonder why I would see Twelfth Night, or any other Shakespeare play, 27 times. The answer is that I've seen 27 different Twelfth Nights. My niece was among many who saw the movie Titanic a couple dozen times, even though the director was always James Cameron at every showing, and Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet never changed their interpretations of Jack and Rose. Who questions how many times people see Monty Python and the Holy Grail or Rocky Horror Picture Show? Tonight I see a Twelfth Night I've never seen before, thanks to the intelligence and insight of this company. And if I were to go to the same show tomorrow night—the last of the play's run at Classic Stage Company—it would be a different Twelfth Night because the cast will be interacting with a different audience. That's the thrill and the art of live theater.

One scene in particular sets this production apart from all other Twelfth Nights, even though the way Fiasco does it seems the obvious way to stage the moment. It comes in the first meeting between Olivia (Austrian) and Viola (Emily Young) disguised as Cesario representing Duke Orsino (Brody) as a love emissary. Olivia asks how Cesario/Viola would woo in her "master's flame." "Make me a willow cabin at your gate," Viola starts in one of the play's most famous passages. Young, speaking the speech with rhythmic resonance, crosses to Austrian and grabs her shoulders, staring deeply into her eyes as she "halloos" Olivia's name "to the reverberate hills." Viola, trying to win Olivia's heart for her master, is all in (and as a woman, she knows better than a male messenger what works). Austrian's Olivia is transfixed: "You might do much," she replies in wonder. And in love. Fixing the physical to the poetical shows us that exact moment's overwhelming emotional intensity that Olivia can never shake off.

And neither will I.

To read the review of this production, click here.

Friday, January 12—Cornered

My Shakespeareances.com copy editor, Carol Kelly, questioned a phrase I used in my announcement of the Canon Project: "This endeavor will cast a wide geographical net, covering every region of the continent corner to corner.” "Or coast to coast?" she commented. She was worried I might sound like a flat-earther.

My phrasing was deliberate: I'm going to the corners of the continent in my quest to see the 38 plays in Shakespeare's Canon at 38 different theaters. Fairbanks, Alaska, is in the works. So is San Diego. Hawaii is in the mix—if I can work it into the schedule, it's part of the continent; if I can't, it's an island chain in the middle of the Pacific. My northeast corner is undetermined, as my intended target's status is in flux, but I have a couple of fallbacks in the queue.

As for the southeast corner, we're on our way there now: Shakespeare Miami to see Hamlet. We've visited Miami before (baseball trips), but this is our first visit to Shakespeare Miami, "Florida's professional Shakespeare company," says its slogan, "Saving the world … One iamb at a time." I love Shakespeare Miami's core values listed on its website (www.shakespearemiami.com): excellence, ensemble, courage, and respect for all. "Shakespeare Miami has a 'No Assholes Rule,'" says the explanation for the last.

The company offers free Shakespeare productions at different open-air venues each weekend this time of year in and around Miami as far north as Boca Raton, Florida. This weekend we will be seeing Hamlet at Pinecrest Gardens, a publicly owned outdoor recreation area with an amphitheater. We're still en route—air traffic today has been hampered by a fog-socked mid-Atlantic corridor—but our plans are to see the play tonight, and then tomorrow take in a sensory-friendly performance, which is the focus of this visit.

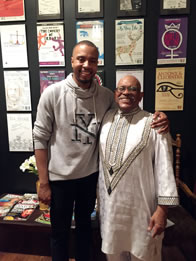

Colleen Stovall, Miami Shakespeare's producing artistic director, has coordinated an opportunity for us to meet with local Shakespeareans and historians who will give us specific insights into Miami's relationship with Shakespeare, which apparently dates to the community's founding.

Sometimes, the corner is a good place to be.

Hamlet, Shakespeare Miami

Pinecrest Gardens,

Pinecrest, Florida, January 13

Where once a large raptor swooped inches over my head from the rafters to the stage, I'm watching Hamlet set a mousetrap for Claudius in Shakespeare Miami's production of William Shakespeare's play—or, rather, a close proximity of his play.

One of the longest tenures of my journalism career was covering the amusement industry, i.e., theme parks, water parks, zoos, and their combinations/variations. I was, for real, a professional roller coaster rider. One of the theme parks I visited was Parrot Jungle, both at its original site in a residential neighborhood south of Miami, and its current location near downtown Miami (in fact, the park flew me in for a private visit a few months before the new location opened to the public in 2003). What I didn't know until today was that the Village of Pinecrest, that residential neighborhood south of Miami, took over the old Parrot Jungle property and turned it into a community recreation park, maintaining the paths, ponds, and flora of the theme park (but not the famous flamingos and its other fauna) and adding a new library and community center. The entire site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

Sarah and I stroll through the grounds and past the original entrance gate, bird cages, and snake houses. The 550-seat amphitheater where Parrot Jungle staged its bird shows has become a venue for concerts (its jazz series is particularly popular), ballet and modern dance, and theater, including Shakespeare Miami, now in its 13th season, which spends one weekend of its four-site tour of South Florida on the premises. It is at times a challenging venue for watching Shakespeare: the acoustics (using stage microphones) can be problematic, the peacocks and peahens congregating on the roof next to the stage can be distracting (though a couple seem intrigued enough to settle in to watch the show), and the constant coming and going of patrons can be annoying. Nevertheless, the palm tree backdrop with fronds sashaying in the breeze, the rough stone-wall-lined amphitheater itself, and a generally appreciative audience, many new to the play (gasps when Polonius falls dead through the curtain), are gift wrap to Shakespeare's verse.

Top, the amphitheater at Pinecrest Gardens in Miami, Florida, with Miami Shakespeare's portable set for Hamlet. Above, the Banyon trees and Patrick Dougherty's Stickwork sculpture (right) adjacent to the amphitheater. Photos by Eric Minton.

Shakespeare Miami's Founding Producing Artistic Director Colleen Stovall, who directed and designed this Hamlet, has set the play in 1920s Denmark, a nation recovering from World War I's devestation and heading for capitulation to Nazi Germany in World War II. Ironically, the biggest chunk of the play Stovall excised to get down to a 2:40 run time (plus 15-minute intermission) was Fortinbras and the Norway threat. The '20s timeframe gives this Elsinore a Great Gatsby look of three-piece suits, capes, and flappers, which has the effect of turning Claudius into an ultracapitalist. That, in turn, brings incredible depth to his not-able-to-pray scene.

Stovall's most significant tweak of the text is transforming Ophelia's mad scenes by defining the term mad not as insanity but fury. In the scenes themselves, this reimagining of Ophelia works textually, but in the big picture it also requires changing the manner and the reporting of her death (and that would require a spoiler alert). Stovall tells me she not only doesn't believe a woman would react the way Ophelia does, she also had never seen the mad scenes work effectively in films and other productions. Thus, Shalia Sakona portrays an Ophelia of the #MeToo era, dealing with harassment from both Claudius and, after their break-up, the seemingly mad Hamlet.

Stovall waited to stage Hamlet until she could land an actor capable of doing the title role, and her patience paid off with Seth Trucks. Hamlet has a lot to deal with, but this Hamlet is also contending with flu-like symptoms of fever, sore throat, and good-god-I-feel-awful malaise. His performance last night was uneven, but today, though suffering physically (which I can confirm upon meeting him briefly after the show), I count him among the great Danes I've seen. His life of late keeps taking peculiarly bad turns, and suicide constantly crowds his thoughts, but he forges ahead on a vague sense of faith. This is the 22nd time I've seen a version of Hamlet on stage, and the first time Hamlet's Yorick speech goes beyond cliché to the psychological resonance that created the visual cliché in the first place.

I targeted this matinee performance of Hamlet because it's announced as a sensory-friendly edition for audience members on the autism spectrum. Stovall describes the protocols. "We don't want to reduce the experience but let them know what to expect," by the actors demonstrating some of the stagecraft before the play, she says. Then, in the production itself, the shouts and violence are toned down. She shows me the safe room where patrons can go for a calming environment yet still watch the play on a monitor if they choose to. Today, however, no one requiring a sensory-friendly performance has signed in, so we get the regular show.

Selfishly, I'm glad, because, Oh. My. God. The Hamlet-Laertes duel in the play's climax is the best stage combat sequence of any production in my recollection (afterward, I learn more about it from Joey Costello, the fight director). The fencing is exquisite, the battle is imbued with the personalities of a feigning-madness Hamlet and a feigning-courtesy Laertes (Lito Becerra turning in one of the production's most dynamic performances), and when it gets intense, effectively-delivered punches supplement desperate swordplay up and down and across the set. It lasts at least five minutes; seems like 30. I wish it were 90.

To read the review of this production, click here.

Sunday, January 14—The Barnacle

Ralph Munroe, who lived on New York's Staten Island, saw a sailboat drifting toward the rocks. An expert seaman himself (he designed 56 sailboats), Munroe sailed out to help guide the boat and its owner, William Brickle, to safety. Munroe asked his unexpected guest where he was from. "Paradise," Brickle replied: Biscayne Bay. Munroe had to see it for himself. When he did, he made Miami his home.

Munroe's house, which he built himself in 1891 (and expanded with a second floor in 1908), calling it The Barnacle because it is shaped like one, is the oldest house in Dade County still on its original site: 40 acres right on the bay and now surrounded by the condos, boutiques, and restaurants of Coconut Grove. Instead of giving in to salivating developers, the Munroe family turned the property over to the state in 1973, which now operates it as The Barnacle Historic State Park. One of South Florida's pioneers (yes, Florida was still a frontier for Americans even after the West was won), Munroe brought with him a taste for arts and culture. He hosted music concerts in his home, and his library included several volumes of William Shakespeare's works, some in languages other than English.

Katrina Boler is park manager at The Barnacle Historic State Park, one of the venues for Shakespeare Miami. Photo by Eric Minton.

Listening to Park Manager Katrina Boler describe the family's and the site's history, I feel like I've formed a first-name relationship with Ralph himself. Boler, with degrees in history and literature, is a big Shakespeare fan. She had her own sailboat-on-the-rocks moment in 2010 Shakespeare Miami's Producing Artistic Director Colleen Stovall called after a last-minute loss of funding for one of the sites where her free Shakespeare production was to be staged. Boler got excited until Stovall told her she needed dates in January, The Barnacle's busiest season. "I looked at the calendar for the dates she gave me, and they were all miraculously not booked," Boler says. "It was serendipity." Miami Shakespeare brought that year's production of The Taming of the Shrew, featuring a high school rock band on stage, to The Barnacle. The company went to other sites in subsequent years but in 2014 returned to The Barnacle with The Tempest.

Talk about a perfect setting for The Tempest: the house (with a brick patio for a stage at the front entrance) faces down a lawn to Ralph's boathouse and the bay, glistening blue on this Sunday afternoon with sailboats gliding back and forth. Thick forest covers the 30-some acres between the house and downtown with a paved path winding through the trees (Ralph considered boats to be the only necessary means of transportation; he hated the railroad and had little use for automobiles). There's even a sailboat on the lawn next to a pavilion that Shakespeare Miami uses as a stage for rainy nights. That boat doesn't belong there. It is a remnant of Hurricane Irma last September, deposited halfway up the lawn by the storm surge. The Barnacle, thanks to Ralph's barnacle design, has survived some vicious hurricanes, but the boathouse took serious damage from the passing boat.

The Barnacle has proved a perfect setting for all Shakespeare Miami productions that have played here, and the two organizations partner on a Shakespeare Birthday event every April. All much to Boler's delight. "The Barnacle gained a lot when Shakespeare Miami lost their stage in 2010," she says. While the mere report of rain can keep people home in South Florida, on nice evenings the plays fill the 2 1/2-acre lawn with 700 to 900 people, Boler says, even though the property has no public parking. Patrons must find a spot somewhere in the busy downtown and walk that path to the house. In Shakespeare Miami's wake, other theater companies have played here, and something called a haunted ballet has also taken hold (I must return to see that someday).

It's all so perfectly Shakespearean, as was Ralph. He encouraged a community spirit by inviting neighbors to his home for concerts and cultural events, perhaps even performances of Shakespeare plays. Shakespeare Miami flips that notion around: the company considers "accessible Shakespeare" to mean not only free and relatable but taking shows to the communities. "It's something for all ages, something on their turf, in their neighborhood, and not a daunting thing like going to a theater," Boler says of Shakespeare Miami's weekend residencies in Coconut Grove. "It brings the community together. You get to sit and laugh together and go 'oh my goodness!' together, which is especially important these days."

Monday, January 15—Warm Thoughts

We're heading home, leaving the warmth of Miami (70 degrees Fahrenheit) toward the 25 degrees the D.C. area will be feeling tonight.

The warmth we're leaving behind is not merely air temperature. The folks at Shakespeare Miami overwhelmed us with welcoming hospitality, and their hosts—the managers of the venues where Shakespeare Miami stages its plays, Jerry Kinsey at Pinecrest and Katrina Boler at The Barnacle Historic State Park—took time out of their busy schedules to show us around their parks and tell their stories. A highlight of the weekend was being treated to a private dinner backstage at Pinecrest Gardens. Shakespeare Miami board members Maria and Paul Eisenhart prepared a fantastic Cuban meal for us (including offering me the pork crackling—now that's hospitality!). “They are the very best kind of board members to have,” Producing Artistic Director Colleen Stovall told me. She and her abiding husband, John Stovall (a faithful volunteer for the cause), joined us along with board members Steve and Cyndy Hill, Florida International University Professor Jamie Sutton, and Doug Wetzel, who plays Polonius in Hamlet.

Thank you, Shakespeare Miami, Pinecrest Gardens, and The Barnacle Historic State Park.

Sunday, January 21—"It Is the Stars," Says Kent

Sunday, January 21—"It Is the Stars," Says Kent

At every opportunity I look for affirmation that this Canon Project is a good idea: feedback from theater folks and friends, my sons drawing on their own particular expertise to lend enthusiastic support, the timing given the significance of 2018 in America and my life. Then there are the omens. I've had so many mystical signs and portents surrounding this quest that Shakespeare would blush to portray them in one of his plays. My dad even appeared to me in a dream and said, "Eric,  just do it," and then laid out a financial plan for the project, which I ended up following.

just do it," and then laid out a financial plan for the project, which I ended up following.

Today I happened upon a "Magic 8 Ball" that we got as a give-away at a Washington Nationals baseball game (it's red instead of black and has the GEICO and Nationals "curly W" logos adjacent to the "8"). I couldn't resist. "Am I going to see all 38 plays in the Shakespeare Canon this year?" I asked the 8 ball.

I pushed the button and turned it over to see the answer: "I foresee a home run."

Friday, January 26—What Shakespeare Means

It still feels early. We left the house just after 6 a.m., and a 2 1/2-hour darkness-into-daylight drive over Interstate 66 and down I-81 has brought us to Staunton, Virginia, a 25,000-people town undulating on Shenandoah foothills. We're downtown, finishing up breakfast at Rèunion Bakery & Espresso (ham and gruyere croissant, oh my goodness!). Across the street is the Staunton Visitor Center on the ground floor of the city's parking garage. Beyond that sits the Blackfriars Playhouse, the world's only re-creation of William Shakespeare's indoor theater in London.

Julie Markowitz , executive director of the Staunton Downtown Development Association, is meeting me in this bakery to talk about Shakespeare: not the man, not the plays, not the industry, but Shakespeare, a term with a Staunton-specific definition. When she was in her 20s and living in Harrisonburg 30 minutes up the interstate from Staunton, Markowitz would hear people say, "Hey, Shakespeare is coming to the park tonight!" Shakespeare was a dozen or so people wearing black turtlenecks and pants and black Converse high-top sneakers performing plays for an audience lounging on blankets and drinking wine. More formally known as the Shenandoah Shakespeare Express, Shakespeare to Markowitz was "youthful, spontaneous, incredible fun energy."

Beverly Street, downtown Staunton's main drag. Below, the Blackfriars Playhouse, home of the American Shakespeare Center (see the closest intersection in the photo above? The Blackfriars is a half block to the left). Photos by Eric Minton.

In the early 1980s, Markowitz lived for a couple of years in Staunton and doesn't have fond memories. Main Street was dying and an adjacent psychiatric hospital (the creepy, old generation of such institutions) was closing, its de-institutionalized residents being moved into subsidized housing downtown. Markowitz remembers being chased to her car every night after work. She returned to Staunton for a job in 1993, and though conditions had improved, she still describes it as dark times.

Then, in 2001, Shakespeare came to town.

In fact, it was the Shakespeare of Markowitz's past. Shenandoah Shakespeare Express built a permanent home in Staunton, making its debut in September 2001. The Blackfriars Playhouse is the perfect environment for the company—founded by Ralph Cohen, a professor of Shakespeare at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, and one of his students, Jim Warren—to stage plays using the theater conditions and staging practices Shakespeare's company would have used between 1590 and 1630. No longer wandering players (though a national touring troupe is still part of its operation) and with a growing education program, the company changed its name to the American Shakespeare Center.

Staunton already had a thriving arts community, says Markowitz, who became executive director of the Downtown Development Association in 2006. Several galleries and theater community groups were operating when the Blackfriars opened, and church concerts were part of the social scene. Arts and entertainment are in the town's DNA. Staunton incorporated in 1801 and became a railroad center in the mid-1800s (today it is at the intersection of Interstates 81 and 64). Warehouses and commercial businesses clustered around the depot; up the hill, the downtown district became the center for hotels, bars, theaters, and other venues of pleasure, arts, and entertainment, inspirational and carnal. Though Virginia is replete with Civil War battlefields, Staunton served as a rest-and-recreation center for both armies, so the town escaped armed combat.

Shakespeare, the man, would feel at home in such a community then, and Shakespeare's arrival in 2001 provided a steroid jolt to the culture and commerce of the town and to the academic and social offerings of Mary Baldwin, a women's college sitting like an acropolis in the center of town. Chefs turned Staunton into a culinary enclave. Small businesses thrived downtown. Next door to the Blackfriars, a derelict hotel, the Stonewall Jackson, was remodeled and expanded as a conference center and designated a historic hotel.

Shakespeare, the man, would feel at home in such a community then, and Shakespeare's arrival in 2001 provided a steroid jolt to the culture and commerce of the town and to the academic and social offerings of Mary Baldwin, a women's college sitting like an acropolis in the center of town. Chefs turned Staunton into a culinary enclave. Small businesses thrived downtown. Next door to the Blackfriars, a derelict hotel, the Stonewall Jackson, was remodeled and expanded as a conference center and designated a historic hotel.

When asked what the Blackfriars most brought to the town, Markowitz doesn't hesitate. "Visitors," she says. Only 15 percent of the Blackfriars audience is local. The American Shakespeare Center has a growing international reputation for the quality and style of its productions and for its education program that brings in students to learn how to stage Shakespeare and teachers to learn how to teach Shakespeare. Many of the theater artists needed for the company's year-round calendar of productions end up settling in Staunton, captured by the combination of small-town atmosphere, a lively cultural vibe, and the surrounding wilderness beauty of the Shenandoah Valley. You want to see the entire Shakespeare canon? Live here.

This is all part of the definition of Shakespeare for Staunton. Nobody calls the entity the American Shakespeare Center or ASC or the Blackfriars or the Playhouse. It is simply "Shakespeare," meaning the place, the product, its people, and their presence. Shakespeare is "a feeling," Markowitz says. "The word Shakespeare conjures up different things for different people. If you're in school and studying, it might be work. If you're in our community and you don't quite understand it, it might mean those artsy people. If you're in my job and you see the impact of it, Shakespeare is the reason people gather. It represents quality, it represents intelligence infused with humor and a sensibility that everybody can understand. He wrote for the common man. He wrote about situations that everybody encounters, and everybody can relate to it. It's couched in this old-world way that a lot of people think is snooty, but it's really not. And I love the way the theater company presents it. It's so high energy, it's so much fun."

She pauses a moment and then strikes home with what makes this Shakespeare stand out. "And I think that it is authentic, so it's fresh." Old is new. Staging plays in the conditions for which Shakespeare wrote them brings out an improvisational vitality long buried by the technology-aided, proscenium-arch, director-centric theater of the past two centuries.

Markowitz thinks back to the "youthful, spontaneous, incredible, fun energy" that Shakespeare brought to her life 30-some years ago. "It's still there," she says of the company that provides a real-time conduit to the man. "They've managed to have a very sophisticated, big business and still maintain in their performances that youthful sort of innocent, lighthearted spirit."

That is Shakespeare in Staunton: a spirit.

Richard II, American Shakespeare Center

Blackfriars Playhouse, Staunton, Virginia, January 27

One year ago to this day, a Friday night in Staunton, Virginia, the actors of the American Shakespeare Company converged on the Stonewall Jackson Hotel's lounge. They were celebrating two members in the company "completing the canon" (playing in every Shakespeare-written play over the course of their careers) with their opening-night performance of Coriolanus that had just concluded next door at the Blackfriars Playhouse. My wife and I happened to be in the lounge when they arrived, and one of the actors sidled up to me and whispered in my ear: "Sarah Fallon is coming back next Ren Season to play Richard II." This for me was a Christmas-morning-Santa-booty moment. Then the actor whispered more: "And Josh Innerst is going to play Hamlet."

One year of excited anticipation culminated today, a day of incredible theater and exceptional Shakespeare. Fallon's Richard is everything I knew it would be, and the ensemble work is exquisitely nuanced. As for Hamlet, well, I'm a guy who spent his formative years attending theater in England, where standing ovations are rarer than comets passing earth. I normally don't stand until the second curtain call, and that only because I don't want to stand out—or sit out (in America, not standing is rarer than comets). Tonight, I rocket out of my seat with hand-hammering applause even before the dead bodies can get up to take their bows. Floating out of the playhouse, I catch up with Joan Saxton, who lives in Sausalito, California, and has come to almost every Blackfriars production a continent away over the past 12 years. She just shakes her head indicating she has no words to offer; her contented smile glazed on an expression of awe more than suffices. We and other patrons walk to the Stonewall Jackson for a formal reception unveiling the American Shakespeare Company's 2018–2019 lineup of plays. The buzz, though, is all Hamlet. People strain to constrain themselves from saying this might be the best Hamlet ever staged.

This is not hyperbole; but now comes the part where the uninitiated are inclined to tell me, "pshaw!" The actors staged both Hamlet and Richard II by themselves in just two weeks.

The company is one week into its annual Actors' Renaissance Season. During the "Ren Season" the theater uses original production practices. Twelve actors with cue scripts (their parts plus a line or two before they speak) put on the play without any director or production team. The cast works out all the blocking and the look of the production in only about a week's worth of rehearsal time. By the end of the three-month season they will be doing a repertory of five plays. This, scholars believe, is how plays were produced in Shakespeare's time, a collaborative effort by the actors. The result is textually pure productions. The actors simply don't have time to contemplate or argue about concepts or interpretations; they have to play what they read, and they have to listen to the other characters on the stage because they have to hear the cues when they arrive.

Key phrases here—"original production practice," "textually pure," "Blackfriars Playhouse" (a re-creation of Shakespeare's indoor theater), "original staging conditions"—would incline many to think this is "museum Shakespeare." It's not: it's closer to improvisational theater with the actors on a mostly bare stage interacting with an audience in the same light (no darkened theater) and in close proximity—patrons even sit on the stage itself. Shakespeare wrote for such conditions and, reportedly, more raucous audiences than today's. How he navigated such an environment with his plot and verse structures emerge during these Ren Season productions, some of the most dynamic live theater—modern, early modern, or Greek—I've seen anywhere.

Sarah Fallon plays the title character of William Shakespeare's Richard II at the Blackfriars Playhouse. Photo by Michael Bailey, American Shakespeare Center.

Richard II is 100 percent verse: Shakespeare even uses rhyming couplets for the comic scene of the Yorks on their knees competitively begging before King Henry IV (David Anthony Lewis). Fallon portrays Richard's crumbling state—his crumbing psychological state as much as his regal one—speaking Shakespeare's most lyrical poetry. Being king is all Richard has known, and he relies totally on divine right, anointed by God, for his political standing. Watching Fallon's Richard discovering that he is as human as everybody else is devastating, no matter how petulant we might think him early in the play.

Casting Fallon as Richard II is a no-brainer. I've admired this actress's work on this stage since 2004. She has portrayed Cleopatra exactly as Enobarbus describes her. Her Lady Macbeth was, along with Judi Dench's, the truest portrayal of the role I've ever seen. She played all four iterations of Queen Margaret in Shakespeare's Henry VI tetralogy produced one part per year over four years, one of the few women to ever do so (a boy or young man would have played the part in the original productions). Her iconic pairings with René Thornton Jr. in several plays (from Tamora and Aaron in Titus Andronicus to Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing) includes Fallon as Cassius to Thornton's Brutus in Julius Caesar: I've never seen the tent scene argument so electric.

Fallon playing Richard II is not stunt casting. Cross-gender casting is common at the Blackfriars. Just as Fallon playing Cassius was all about chemistry with Brutus, to Jim Warren, the American Shakespeare Center's artistic director through last year, Fallon is perfect for Richard because of her verse-speaking skills and her abilities in portraying regality and psychological disintegration—even at the same moment, as she does in the deposition scene at the center of Richard II. Critics often see Richard as an effeminate tragic hero, but Warren knew Fallon wouldn't play the part that way. I've seen Fallon effectively lead armies, torture dukes, go toe-to-toe with Richard III, beat up messengers, psychologically castrate Scotland's greatest warrior, and, in Beaumont and Fletcher's The Maid's Tragedy, physically castrate a king, all while playing women; and I've seen her manage and participate in a successful assassination plot while playing a man.

Here she's playing a king. Sure, Richard is spoiled, loves flattery, is inefficient in governance, and not politically astute, but he keeps a firm grip on his core ethic, divine right. In the final scene he fends off four murderers, killing two of them before being fatally stabbed himself. That moral strength and physical danger runs through Fallon's performance from the start. I knew she'd be scary good as Richard II, and the payoff has been one year coming.

To read the review of this production, click here.

Tuesday, January 30—A Shot in the Arm

It took two, big, burly corpsmen and my father to hold me down as the doctor gave me a penicillin shot when I was 7 years old. My distaste for needles hasn't abated since. Bravery for me was getting a vaccine during a hepatitis outbreak on the Air Force base in Alaska where my father was stationed when I was a young teen. One of my classmates had been stricken, so I weighed the odds—and gave in only to the base commander's orders for all families to get the shot at the base clinic.

I've never gotten a flu shot. I've also never had the flu. Heck, I average a cold only once every three years. But I've had three colds already since October, and there's been a particularly virulent strain of flu going around the D.C. area and down in Staunton, Virginia, where we were this past weekend. Today, when I was at a doctor's appointment for an unrelated matter, the nurse asked, "Have you had your flu shot?" "No," I mumbled, knowing I would have to explain myself and still get a lecture. "Would you like one today?" she asked.

My life flashed before my eyes: not my past but my future, cramming as much as a dozen Shakespeare plays in a dozen locations into the next three months. "Yes," I heard myself mumble. Holy cow, I just agreed to get a shot! How's that for dedication? Honestly, I didn't feel a thing when she gave me the shot. Not that I'll volunteer for future needling, but 53 years of imagined terror seems kind of silly to me now.

Wednesday, February 7—It's a Puzzle

My parents once gave me a jigsaw puzzle of the moon. I've never been good with jigsaw puzzles. I was in junior high school at the time and I didn't think to report them to social services. Then my wife, Sarah, topped them: one Christmas a couple decades ago she gave me a 500-piece, double-sided jigsaw puzzle of The Beatles eponymous LP—better known as "The White Album." It's still in its shrink-wrapped box. She's still my wife, too.

And now I'm staring at my Shakespeare Canon Project matrix.

Traveling back and forth across the land, seeing all that Shakespeare and visiting all those theaters, what fun! Planning it all out, not so much. It is part of the adventure, but in manner much like Alaska's giant mosquitos that suck on you as you hike through that land's majestic splendor (something I can look forward to in late July).

Timing, I knew, would be the biggest contention. So many productions were bound to land during festival season, June through September. It's worse than I imagined, however. Most of the productions—including so many on my "must do" list of priority theaters and only-playing-there titles—have their runs in a three-week period from the end of July into August. The Major League Baseball All-Star Game on July 17 hosted by our Washington Nationals is further exacerbation. Attending an All-Star Game has been one of our primary baseball goals, and when the Nationals were announced three years ago as hosts for 2018, we became season ticket holders to get first crack at tickets. It's not just the game; it's four days of festivities and showcase games from Saturday through the main event Tuesday night. As soon as Major League Baseball set those dates last August, I booked a hotel room across from the downtown ballpark. At that time, seeing the Shakesperae canon in one year was a fleeting wish. Now, the All-Star Game is trimming significantly my canon-completing opportunities.

Back to the matrix. I'm working with several different priorities. Number One, to see all 38 plays in the traditional canon (the First Folio plus Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen) and productions of Shakespeare's poetry and apocryphal plays as a bonus. Equal priority is to see each play in a different theater. Next priority is to cover the breadth of the land, starting with the four corners of the continent: Miami (done), Fairbanks, and San Diego are on the table, as is Hawaii if I can work out the schedule (I'm quibbling with the definition of continent here). As for the northeast corner, my preferred theater, Shakespeare by the Sea in Newfoundland, is currently in flux, but I have geographical fall-back options. I aim to get to at least two productions in each of 12 regions: New England, New York Metro, Middle Atlantic, Deep South, Mid-South, Industrial Midwest, Agricultural Midwest, Rockies, Southwest, West, Northwest, and Canada. Except for the last, these regions have blurry borders. I also intend to limit myself to no more than five productions per region, but the midsummer traffic jam of plays I see ahead of me might detour me off these standards. After consideration of geographical spread, I'll focus on covering a full spectrum of theater spaces, production styles, and company compositions.

With about 30 theaters linked on Shakespeareances.com still to announce their 2018 titles, five plays have not yet shown up on this year's playbills: The Two Gentlemen of Verona; Henry VI, Part Two; Henry IV, Part Two; Cymbeline; and Henry VIII. Ironically, it's not lack of plays but too many productions of the same play that's giving me fits. So many theaters this year are doing All's Well That Ends Well, Love's Labour's Lost, and King John. Then there's Macbeth, not only with productions aplenty but a great variety in styles: the experimental version at Shakespearemachine in Fort Wayne, Indiana (in November, yes!), or the Elizabethan stage setup at Lake Tahoe (by the lake, yes!), or the Aaron Posner and Teller version at Chicago Shakespeare (in the new theater, The Yard, yes!).

All these Macbeths, but not necessarily enough Shakespeare variety to spread out my calendar or attain my regional goals. When Sarah and I were first laying out our ideas for the Canon Project, we had a short list of theaters and festivals we wanted to visit, some longtime favorites, some places we have never been (in fact, one of my goals is for at least half of the productions I see to be at venues new to me). Idaho Shakespeare Festival in Boise was on that short list; we've been there twice and love the theater and the productions. However, for 2018, of the five plays the Idaho Shakespeare Festival is staging, only one is by Shakespeare: yep, Macbeth. This is a notable trend at Shakespeare-named theaters. Of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival's 11 titles this year, only four are by the namesake playwright, plus one about the namesake playwright. At least they're not doing Macbeth, but three of their four Shakespeare titles I've already assigned to other theaters: Romeo and Juliet (I'm opting for the choose-your-own-ending version being presented in a bar next week), Othello (I'm opting for an original pronunciation version in April), and Henry V (I have two more intriguing options that I can't reveal as one is not yet publicly announced). That leaves Love's Labour's Lost, which, if I choose that one, several other preferred theaters come off the chart.

Ultimately, many of my final selections will come down to time and travel: when can I get where, and where can I get when. Even my desire to get to the continental corners will have to contend with that reality.

Puzzles. At least they look good when they're done.

Friday, February 9—A Web of Imogenation

Yay! Fist-bump-times-eight the spider! Insider information assures me a Henry IV, Part Two, is coming to a stage late this year, and The Two Gentlemen of Verona showed up on a playbill as I caught up Bard on the Boards this week. Just three Shakespeare Canon titles have yet to find a home in 2018: Cymbeline, Henry VIII, and Henry VI, Part Two.

Piecing together my calendar provided a mix of bad news and good. As I expected, the run dates of so many plays appearing at only one theater this year fall between July 19 and August 5. Meanwhile, a couple of regions ended up lacking representation on the calendar. I will have to forego a couple of really-want-to-see productions, sacrificing my own preferences for the greater cause. Nevertheless, laying out the calendar of potential productions brings this project's ultimate goal into clearer focus. I will be able to see every play in the Shakespeare Canon that is produced on the North American continent this year, plus at least three apocryphal plays, each produced by a different theater company. It will take a lot of hustle, but the goal is within reach. I just need those last three missing titles to be staged somewhere.

In a seemingly unrelated matter, this week I also posted my review of the Folger Theatre's production of The Way of the World, Theresa Rebeck's modern adaptation of William Congreve's Restoration Era comedy. The production is part of the Women's Voices Theater Festival here in the Capital Region, with 24 companies currently staging plays written or directed by women. As I was about to toss the play program into my recycling bin, I glanced at the festival flyer, and a title caught my eye: Imogen.

Pointless Theatre in downtown Washington combines puppetry and other graphic elements with live action in its productions, and this particular outing does so with Shakespeare's play Cymbeline. The adaptation further retitles the play to focus on the play's true leading character, King Cymbeline's estranged daughter, Imogen. However, the play's run ends this weekend. Can I get tickets?

Yes, I can! So now, Cymbeline is in the fold for the Shakespeare Canon Project, and I don't have to fly cross-country or try to squeeze it into a three-week, cluttered window in late July. Serendipity strikes again. High-five the spider, post this update, and head downtown for an evening with Pointless Theatre.

OK, about Spider. My dad had this plush toy spider next to his computer in his home office. I don't know when it showed up, where it came from, or anything about its backstory. My mom  collected teddy bears and other plush animals, and because of her obsessive-compulsive nature she had more than 3,000 such critters of varying sizes and species at the time of her passing. "Spider" may have been one of them (she named all of her bears, but I never heard the spider named). Dad obviously was attached to it. When Mom and Dad moved to their retirement center, Spider was one of the first items he packed in his office and unpacked in their new apartment. After his stroke, Dad had to move out of his apartment to the center's assisted living wing, and Spider accompanied the computer upstairs. Near the end of his life as his condition deteriorated, Dad twice had to move to a new room for increased levels of care, and he would grab Spider and make sure it didn't get waylaid (he may have suspected I was coveting it; he would have been right).

collected teddy bears and other plush animals, and because of her obsessive-compulsive nature she had more than 3,000 such critters of varying sizes and species at the time of her passing. "Spider" may have been one of them (she named all of her bears, but I never heard the spider named). Dad obviously was attached to it. When Mom and Dad moved to their retirement center, Spider was one of the first items he packed in his office and unpacked in their new apartment. After his stroke, Dad had to move out of his apartment to the center's assisted living wing, and Spider accompanied the computer upstairs. Near the end of his life as his condition deteriorated, Dad twice had to move to a new room for increased levels of care, and he would grab Spider and make sure it didn't get waylaid (he may have suspected I was coveting it; he would have been right).

Upon Dad's passing, I took custody of Spider. It now sits next to my office computer. Because my dad's legacy is largely inspiring me to do the Shakespeare Canon Project, Spider serves as the physical representative for my father's spiritual presence, even accompanying me on my travels. He's a spider: he fits easily in my bags and likes tight spaces.

Imogen (née Cymbeline), Pointless Theatre

The Dance Loft on 14, Washington, D.C., February 10

We start our interrogation of William Shakespeare's feminist cred by challenging his choice of title for this play, Cymbeline. At 290 lines, the titular king of Britain speaks just 8 percent of the script. His daughter, Imogen, has more than twice that: 594 lines which, at 16 percent, is so dominant that the next-largest speaking part, her husband Posthumus Leonatus, gets 12 percent of the total with his 442 lines (I'm indebted to ShakespeareWords.com for line counts and the Royal Shakespeare Company's edition of William Shakespeare Complete Works, edited by Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen, for percentages). King Cymbeline, in his own play, is such an insignificant puppet manipulated by the Queen, Imogen's stepmother, that Pointless Theatre's production of the play presents him as just that: a hand puppet manipulated (and spoken) by the Queen (Hilary Morrow).

It's more than just word counts. This is Imogen's play, her story. All plot threads—the banished husband, the chastity wager, the court intrigue, the lost princes, Rome's invasion of Britain—wind through Imogen on their way to being audaciously tied up in Shakespeare's deftest denouement. By titling her adaptation Imogen, Charlie Marie McGrath, who also directed, is setting the record straight, a starting point for not only honing the play's focus on Imogen but also revisiting Shakespeare's tragicomedy through a woman's lens.

The Dance Loft on 14 is a complex of dance studios plus a small theater upstairs in a building housing a mattress showroom on 14th Street in Northwest Washington, D.C. Pointless Theatre uses this space to stage its production of Imogen, an adaptation of William Shakespeare's Cymbeline. Photos by Eric Minton.

This production is part of the Capital Region's Women's Voices Theater Festival during which 24 theaters in and around D.C. are staging plays written and directed by women. As McGrath is doing with her retitled version of Cymbeline, the Women's Voices Theater Festival is intended to highlight the too-often-downplayed role of women in theater, what McGrath calls in her Imogen program notes, "a correction of a deficit, a need, a desperate need to put women's voices at the forefront of 21st century American theater."

With Imogen, the nine-year-old Pointless Theatre is making its first foray into Shakespeare. Our getting to the company's current space, The Dance Loft on 14, is a foray in itself, though it's only 30 miles from our house. We give up on our confounded GPS to find street parking in a two-block business district of 14th Street that traverses this mid-20th century Northwest D.C. middle-class residential area. We park in front of a mattress store housed in a drab-yellow Mediterranean-style building. Across the street is the bus barn, resembling a gothic fortress, for the Washington Metro Area Transit Authority. As I look about, Sarah spots a banner over the mattress showroom entrance: "The Dance Loft on 14." Imogen posters point us to the door, and up the stairs we reach a complex of dance studios and the 68-seat theater where Imogen is playing, all carved out of what appears to have once been a 1930s-era ballroom.

Pointless Theatre productions merge live action with shadow puppetry while layering scripts with heavy doses of music and movement. McGrath, a product of Chicago's rich theater scene and assistant director for several productions at the Shakespeare Theatre Company in D.C., approached Pointless Theater about applying their aesthete to her idea for remaking Cymbeline. In addition to casting Cymbeline as a hand puppet, she uses shadow puppetry to illustrate off-stage elements of the plot, such as Leonatus, on his way to banishment, fighting with Cloten, and Guiderius, represented as a bear, knocking off Cloten's head in the Welsh woods. The production begins in a fairy tale world with the medieval look of a children's book but transforms into modern dress as the play progresses.

Two musicians sitting in the corner of the stage provide a constant soundtrack of music and environmental sounds (composed by one of the musicians, Pointless Company Music Director Michael Winch). Choreographer Ryan Sellers creates mime and dance sequences for Fidele's funeral, the battle between the Britons and Romans (including strapping on body armor and then, locked and loaded, crouching with bent elbows to represent bearing rifles), and Imogen's disguising herself as Fidele, a nightmarish trip for the woman as the ensemble strips and re-dresses her on stage.

Think about that: for Katelyn Manfre's determined and intelligent Imogen, becoming a man is a bad dream. “I am nothing,” she says soon after; “Or if not, nothing to be were better.” She's witnessed in abundance how the XY chromosome combination creates nightmarish figures. Her father is a peevish blowhard. Her stepbrother is a crude lout with a violent temper. Her husband has accused her of adultery and wants to kill her for it. Iachimo is a slimy self-styled stud (which comes across to women as, simply, a slimy jerk). Emerging from the trunk in Imogen's bed chamber and wearing gloves with elongated fingers, Iachimo does more than just note her bed chamber, take her bracelet, and inspect her body: he slips those elongated fingers up Imogen's nightdress for his own private climax.

Not all men are bad. The two princes are pure honor and adorably played by Renaldo McClinton as Guiderius (who sheds real tears as he dances Fidele's funeral) and Kevin Thorne II as Arviragus (who sings the funeral dirge, the production's most moving moment, spurring those tears in Guiderius and some in the audience, too). But, then, living with their supposed father out in the Welsh woods, they don't bear society's imprint (nor has Imogen met them yet). And in this production, it's not their supposed father but their supposed mother: Belarius (Lee Gerstenhaber) has been re-gendered, as has Leonatus' trusty servant working for Imogen, Pisanio (Acacia Danielson). That alone infuses the play with female perspectives as the lines they speak or are threatened with take on #MeToo and Children's Health Insurance Program significance.

McGrath's adaptation remains relatively true to Shakespeare's text, though many lines are transplanted within the play and from other plays. She also transfers passages to a different character to suit her thematic purpose. It is Imogen, not Leonatus, who forgives and pardons Iachimo at the end (but, then, Leonatus doesn't seem capable of doing that), and it is Guiderius who pardons the Romans. Cymbeline has retired, a la Lear, leaving the princes and princess to rule in equipollence. "Never was a war did cease, ere bloody hands were washed, with such a peace," Imogen speaks the final line. A fairy tale ending, perhaps, but not pointless.

To read the review of this production, click here.

Coriolanus, Brave Spirits Theatre

The Lab at Convergence, Alexandria, Virginia, February 10

It wasn't that I miscounted, I just didn't recount. For more than a week, my upcoming trip to Connecticut would take me to my 500th staged William Shakespeare production. I was at 498, and a production of Coriolanus by Brave Spirits in Alexandria, Virginia, was coming up on this Saturday night, but not as part of the Canon Project.

Brave Spirits had originially been the representative theater for Coriolanus, but when late this week I inserted Pointless Theatre's Imogen into the matrix, my need to spread out the Canon Project's geography trumped my desire to profile Brave Spirits. That was a hard call for me, too, as this company is one of my favorites, and it plans to stage the entire Shakespeare history cycle as a repertoire in 2020, a sequential staging of the eight War of the Roses plays reflecting on current political conditions. That's exactly something I've envisioned since I was in college (in every age of man, "current" political conditions are always fraught, it seems), and I want to give Brave Spirit's ambitious "History Is 2020" project wider notice. Nevertheless, I had another Coriolanus glowing on the matrix, a Stratford Festival production in Ontario already generating buzz before opening. Stratford was my initial choice to see Julius Caesar, but there always comes such another Caesar.

So, Brave Spirits dropped off the Canon Project itinerary. Still, this production was a significant one in my lifelong Shakespearean trek. By inserting Imogen and seeing it this afternoon, tonight's Coriolanus is now my 500th Shakespeare production. That doesn't occur to me as I wait in the theater lobby wondering why, five minutes before showtime, the theater has yet to open for seating.

Then something more significant than a benchmark number happens: The plebeians start uprising—in the lobby. The small room barely has enough space for patrons, and now the first scene of Coriolanus is playing among us. I jerk as a firm hand clasps my shoulder from behind. "What work's, my countrymen, in hand?" the man attached to that hand says to me. It's Menenius, and he moves on into the room to address the rabble. Ian Blackwell Rogers, a longtime fave of ours, is playing Menenius, and he chooses the target for his entrance knowing he would not get punched or sued. Things really get intense in that little room when Caius Martius himself (later to become Coriolanus) arrives. Looking around the room, I notice that the nonactors are worried: they might have to choose sides if a real riot breaks out. But, no, the action is moving to the capitol, Martius bids us follow, and we do—except in the hallway to the theater, the newly elected tribunes, Sicinius and Brutus, waylay us to worry openly about Martius.

Only then, for the play's second scene, do we enter the theater, its 52 seats arranged in a square. A couple of seats already are occupied. I sit next to a woman stitching a pair of pants. This turns out to be Virgilia (Renea S. Brown), wife of Martius. The play continues in the same manner as what we experienced in the lobby, scenes exploding from behind and among us into the center of the play space. Virgilia doesn't leave her seat as she plays her entire scene with Martius's mother, Volumnia (Jessica Lefkow). The knife fight between Martius and Aufidius (Robert Pike) takes place on the floor a couple of feet from us. For the second half of the play, Aufidius takes the seat next to me where Virgilia had been sitting. Pike plays Aufidius as a coiled cobra, and I spend much of the rest of the play wondering when he would snap my head off at the mere memory of a fight he lost to Martius some years back.

Fourth-wall-shattering theater is no longer a novel concept, though the large number of companies that still strictly adhere to proscenium arch conventions might make you think otherwise. Fourth-wall-shattering was standard practice in Shakespeare's time, but these days it's often treated as theatrical calisthenics—gimmickry. Brave Spirits Artistic Director Charlene V. Smith, who helms this production of Coriolanus, does not indulge in gimmickry. She explores Shakespeare's texts with both a trust and openness that results in some of the most stimulating Shakespeariences I've known. She does so again with this Coriolanus.

This is a play of the people. Literally: the word people is spoken more than 80 times. It's used with both positive and negative connotations, as a badge of honor and an entity to scorn. Nevertheless, this play is peopled with equal representation from all classes and different countries, too. Coriolanus has famously been staged as an exemplar for political positions across the entire spectrum of ideologies, from communism to fascism. Smith doesn't assign any person or party as righteous or villainous, nor does she assign us, the audience, to any particular faction. She integrates us into the whole of Roman (and Volscian) society. In that opening scene in the lobby, the rabble direct their distrust at us, Menenius directs his parable at us, Martius directs his scorn at us, and the two Tribunes engage us in their concerns. Which side are we on? Everybody's.

O Martius, Martius! Would that this production represented you in the Shakespeare Canon Project. (A domino effect later this year would make this so.)

Wisely or not, I am not restricting my theater attendance this year just to the Canon Project itinerary. We have subscriptions to Brave Spirits and other theaters in the region, and while visiting a company on the Canon Project itinerary, I intend to see as many of their productions as I can fit in. This means a few more scheduling headaches and a lot more work, as I plan to review for Shakespeareances.com all the plays I see, but it pays off in the experience. Just six weeks into the year, in addition to four Canon Project plays, I've attended a Hamlet (American Shakespeare Center) that is among the best theater experiences I've ever had, and now I've seen Brave Spirits' scintillating Coriolanus.

That Hamlet was Shakespeare stage production number 498 in my lifelong tally, and this Coriolanus is 500. The benchmark doesn't mean nearly as much as the ongoing proof that you can never see enough Shakespeare.

To read the review of this production, click here

Wednesday, February 14—Flurple Reigns

Yes, it's Valentine's Day, and I'm apart from my valentine here in Shelton, Connecticut. So what? She was in the Air Force. I'm a journalist. For the first dozen years of our courtship and marriage, we didn't spend a single Valentine's Day together. She was deployed or doing distant duty somewhere, or I was traveling on assignments. For many of the past half dozen years, my dad-care duties had me away from home on Valentine's Day, too. Even when we do happen to be home together on February 14, we treat it as just another day—probably because we approach every day of the year as our Valentine's Day.

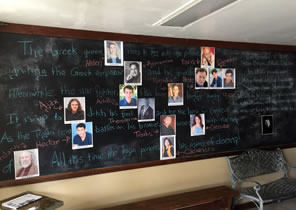

Valley Shakespeare Festival Founding Artistic Director Tom Simonetti (center with script) leads the cast into the multitrack script of Romeo and Juliet: Choose Your Own Ending by William Shakespeare, Ann Fraistat, and Shawn Fraistat during rehearsals in Shelton Connecticut. From left: Sam Plattus (Benvolio, Capulet), Ella Smith (Juliet), Jeremy Funke (Mercutio, Nurse), Jack D. Martin (Tybalt, Paris, Montague), Jessica Breda (Rosaline, Friar Laurence), and Killian Meehan (Romeo). Photo by Cheryl O'Brien, Valley Shakespeare Festival.

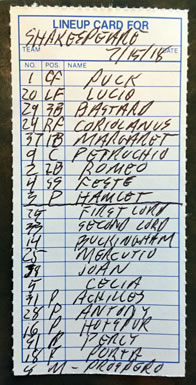

I spend all of today with Romeo and Juliet—and Mercutio and Nurse, Tybalt and Paris, Benvolio and Capulet, Montague and Friar Laurence, and an unexpectedly inordinate amount of time with Rosaline. Today has been day three (of 3 1/2 days total) for the Valley Shakespeare Festival's six-person cast, plus Artistic Director Tom Simonetti, to rehearse Romeo and Juliet: Choose Your Own Ending before their performance at Tavern 1757 tomorrow night. The play by Ann Fraistat and Shawn Fraistat (and William Shakespeare, of course) stops at three points for the audience to vote on the fate of the young lovers, starting with whether Romeo should pursue Juliet or stay true to Rosaline. That means a total of eight different potential endings—a one-hour show with a 147-page script. For a one-night-only performance, Simonetti and the actors have to rehearse each track. Just the logistics of keeping the blocking straight is mind-blowing, and seven-eighths of what they are working on today will not see the public light of day.

Turns out I have a lot at stake in the audience's votes tomorrow night, too. I've seen all the endings, and one stands out for its brilliant hilarity: the flurple ending. I saw it once in rehearsal today, and I want to see it again. I get my chance at the end of the day. For their single run-through at the end of a nine-hour rehearsal, I serve as the audience, voting on which turn the play would take. It's a lot of responsibility, especially as the script includes direct-address reminders to the audience that characters' fates are in their hands so don't [screw] it up. This is an adult-language play, so it's disconcerting to have actors level the f-word with the full force of a glare directly at me. Though I knew which conclusion I wanted, I hadn't figured out how all the tracks pieced together (as I said, the logistics are mind-blowing, and I'm not playing in or directing it). My choices led to the one happy ending for Romeo and Juliet and Rosaline and Mercutio and Tybalt, too. The only one here not happy was me: I didn't get to see the flurple ending again.

So, on this Valentine's Day night, my loving energy goes out to tomorrow's sold-out audience at Tavern 1757; may your votes lead us all to a flurple ending.

Romeo and Juliet: Choose Your Own Ending,

Valley Shakespeare Festival

Tavern 1757, Seymour, Connecticut, February 15

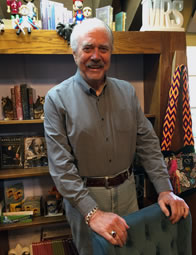

Tom Simonetti is from The Valley, a cluster of small cities and large towns along the Naugatuck River. Its population is mostly working-class people, resiliently powering through the economic ebbs and flows of the past several decades and dedicated to their community, which, though comprising the municipalities of Seymour, Derby, Ansonia, and Shelton, they consider collectively as The Valley. Though located in southwest Connecticut almost equidistance between New York City and Hartford, The Valley is isolated from a mass transit perspective. Valley residents might have an appreciation for culture but no convenient access to the cultural institutions of the Northeast Corridor.

Tom Simonetti, founding artistic director of the Valley Shakespeare Festival, stands at the Tavern 1757 bar before his production of Romeo and Juliet: Choose Your Own Ending. Photos by Eric Minton.

Simonetti is a theater artist, an actor and director who honed his craft in New York. He also has Valley DNA. From the time he was in college he dreamed of bringing a Shakespeare festival to The Valley. Even if he didn't sense a demand, he knew the need, and as he was nearing his 30th birthday, he founded the Valley Shakespeare Festival and staged its first free play, The Comedy of Errors, for one weekend in the summer of 2013 in downtown Shelton's Veterans Memorial Park. Simonetti estimates a hundred people showed up that first night. Each night, the crowds grew. They continue to grow, now averaging 400 to 500 per show, even in rain.

One person who attended that first year was Mark S. Holden, an insurance agent and chairman of the Shelton Public Schools. Growing up in nearby Trumbull, he remembers a Shakespeare acting troupe visiting his school with "gorgeous costumes and props and absolutely horrid actors, people who knew their lines but didn't know what they meant." Most of his life he "knew Shakespeare was someone I was supposed to like," but he didn't know why until he saw Simonetti's new company play Shakespeare with "$50 worth of costumes and props and great actors." He approached Simonetti about taking his productions to the schools.

This played right into Simonetti's dream. He didn't just want to do free Shakespeare in the park of his hometown. He wanted to build a local institution, one with a professional (i.e., Equity) foundation, one with a workable business plan, one that would address the needs of literacy and access to theater throughout all elements of Valley society. "The schools always want them back," Valerie Knight-Di Gangi, program officer for the Valley Community Foundation, told me earlier in the day. "Schools can't afford the time or resources to bring people back unless it's worthwhile." This worthwhile endeavor has spread to other institutions throughout The Valley: libraries, senior centers, and homeless shelters, conducting workshops in addition to performing.

And bars, too. Valley Shakespeare Company will do one or two plays in taverns during the winter. Simonetti and company believe the plays are a perfect fit for such an environment. Imagine mutilated Lavinia walking among the tables in Titus Andronicus or Falstaff hanging out at the bar during The Merry Wives of Windsor, both of which the Valley Shakespeare Festival has done. One establishment, in fact, begged out of future shows because the crowds overwhelmed operations.

And bars, too. Valley Shakespeare Company will do one or two plays in taverns during the winter. Simonetti and company believe the plays are a perfect fit for such an environment. Imagine mutilated Lavinia walking among the tables in Titus Andronicus or Falstaff hanging out at the bar during The Merry Wives of Windsor, both of which the Valley Shakespeare Festival has done. One establishment, in fact, begged out of future shows because the crowds overwhelmed operations.

Tonight, Holden is sharing a high table with me at Tavern 1757. We are among the 80-plus people who have filled to capacity the restaurant's upstairs banquet room (with a bar) to see Romeo and Juliet: Choose Your Own Ending, a one-hour adaptation of Shakespeare's play by Ann Fraistat and Shawn Fraistat. Three times in the play, the audience votes on a decision Romeo must make. The play continues with the audience directing Romeo into one of eight endings, ranging from everybody living and happy to everybody dying and angry. The Fraistats supplement Shakespeare's verse (mostly from Romeo and Juliet, but other plays, too) with some modern applications of thou and thine. Nurse identifies Juliet to Romeo or Benvolio (depending on the track) with "Marry, bachelor, her mother is the lady of the house, and a good lady, and a wise and virtuous. I nursed her daughter that you talked withal. So whate're you're thinking, Montague, hands off!" The play is also infused with clever digs at Romeo and Juliet's own plot, characters, and conventions.