Judi Dench Tackles

Her Greatest Role:

Judi Dench

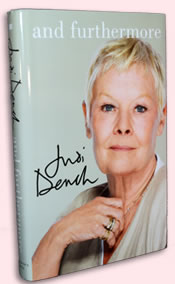

And Furthermore

And Furthermore

Judi Dench (St. Martin's Press, 2010)

Babe Ruth became one of the most popular personalities in the history of sports, but think about how many people actually saw him play. Yes, he packed stadiums and barnstormed America and other countries, and newsreels occasionally captured him on and off the field. Still, the majority of people who revered Ruth knew of his slugging exploits only by reading or hearing about them.

Many of the great Shakespearean actors through the centuries—Burbage, Garrick, Kean, Siddons, Booth, Tree, and Bernhardt—similarly have entered our knowledge base only by what people said about them, not what any of us saw in person. This is true even of the great performances of the 20th century from Gielgud, Olivier, and Ashcroft.

Judi Dench, too. I came to my own reverence for Judi Dench through report. Sure, I saw her as Titania in the filmed version of Midsummer Night's Dream, in which what she wasn't wearing was more memorable than what she was acting. I saw her on stage as Adriana in Trevor Nunn's famous musical version of The Comedy of Errors at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1977, in which Dench was just one of many memory-searing elements of that production. Rather, it was my parents talking about seeing her Beatrice opposite Donald Sinden's Benedick and her Lady Macbeth opposite Ian McKellen, along with constantly reading references to her Viola, that established her greatness in my own mind.

So when I moved to England with my first wife a decade later, one of the first plays we saw was with Dench and her husband, Michael Williams, as Mr. and Mrs. Nobody—an evening of theater that, to this day, I can not recall at all (even after looking at the program and reading her memoir and biographies). Maybe that's like somebody seeing Ruth at Yankee Stadium for the first time, and he goes 0-3 with a walk. But my next experience of Judi Dench was her Cleopatra at the National Theater, and that was a five-home-run evening that still reverberates for me and anybody else who saw it. With that, I have passed on the Dench mythology to my sons, though they could see her skills for themselves in the films Mrs. Brown, Shakespeare in Love, Iris, and Chocolat.

Dench herself refers to such mythologizing in her memoir And Furthermore as she talks of the Mount Rushmore of acting greats ruling the boards when she made her professional debut as Ophelia with the Old Vic in 1957. “I love that mystery surrounding certain actors,” she writes. Yet, this “mystery” turns out to be, for me, one of the shortcomings of her memoir. I want to learn about that unfathomable something that made her Cleopatra the greatness it was; I want to know the where, when, why, and how (and with whose help) her great performances were formed. To my query, she has a firm reply on page 238 of her book: “I think that's none of the public's business,” she writes. “In any case, I never know why I've done something, it's for lots of reasons. I want to keep a quiet portion inside that is my own business, and not anybody else's.”

Dench is the greatest Shakespearean actress of her generation and a couple of generations before and after. Many critics would even drop the “Shakespearean” qualifier, as Dench has triumphed in many non-Shakespeare plays, on the TV screen from sit-coms to avant-garde teleplays, and on the big screen from Queens Elizabeth I and Victoria to James Bond's boss, M. Great actress that she is, though, does not translate into a riveting memoirist. In a year that saw memoirs as great literature (Andre Agassi's) and great illiterature (Keith Richard's), Dench's comes up short because, simply, she doesn't like talking about herself.

Thus, don't look for And Furthermore as a tell-all memoir. Mostly, in fact, it is a retell-some memoir, for much of what's in this book repeats the anecdotes found in earlier biographies—sometimes word-for-word, as And Futhermore is authored by Dench “As told to John Miller,” who wrote or edited three of the predecessor books. She does add on another five years of her life with this book, but she races through the films and plays of this time in two-paragraph strides.

Still, because Dench is notoriously private (while being famously genuine in public), we experience genuine delight when she occasionally pulls back the curtain just a smidgen on her creative thought process and allows us to glimpse inside. Often, though, the peek stops with a larking digression. Why has she never played in a Greek play? “I don't fancy playing in a mask,” she writes.

A couple of times we're allowed a longer look, and these are golden, like learning how Trevor Nunn's seminal Macbeth came together (and how he didn't want to do it in the first place), or how Hal Prince guided her in triumphing as Sally Bowles in Cabaret despite her limited singing abilities. With surprising detail, she goes into the personal and professional turbulence of directing, rather than acting in, a play (Much Ado about Nothing starring Kenneth Branagh). She describes her interpretation for playing Lady Macbeth as vulnerable rather than confident, which she finds in the text, and she intriguingly says that if she could play Bernard Shaw's St. Joan again, she'd make her a troublemaker. She also discusses the difference in craft between playing Shakespeare and acting in a TV sitcom, which she finds much more challenging than any role The Bard has written.

Granted, as she writes, “Acting is such a personal, imperfect kind of art,” and we have to merely wonder with her why her Beatrice always got laughs, inappropriately, on the line “Kill Claudio,” while Samantha Bond's Beatrice, directed by Dench, got the audience to gasp with the line. Still, it's her sense of privacy rather than any mystery that usually closes the curtain on us. For example, she begins writing about her husband's lingering illness and death from lung cancer, obviously a huge heartache for her, but in two pages we are not only beyond that episode but sensing no impact, lasting or otherwise. Director Greg Doran opined in the tribute book Darling Judi (click here) that dealing with Williams' death informed her portrayal of the Countess of Rossillion in All's Well That Ends Well. In her own memoir, though, Dench gives scant mention to her playing the part, a portrayal considered by critics to occupy the upper tier of her great Shakespeare roles alongside Juliet, Titania, Viola, Beatrice, Lady Macbeth, and Cleopatra.

This is not to say we don't get her opinions. She weighs in on everything from actors going on stage while sick with the flu to coughing audiences and their cellphones. She sprinkles such observations throughout the book, and often returns to her overarching lesson that, whether it is a stage, television, or film production, good camaraderie among the actors pays off in the success of that production. “An audience will always register if members of a company have a rapport with each other,” she writes, an observation I can second in all the theater I've seen.

She also more than willingly lets us see her frailties, from her famous penchant for clumsiness to occasionally dropping a half page of script in performance (including skipping over the entire “A handbag?!” revelation as Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest). She freely admits that she often finds herself copying actresses who have played a part before her. Then there is her recollection of playing Lona Hessel in Ibsen's Pillars of the Community to McKellen's Karsten Beernick: “All I can remember is that I had red boots, whistled, and had a vaguely tartan dress; I can't recall a single thing about the story.” I'm strangely comforted by that admission.

Plus, of course, there's the theater and on-set anecdotes and the practical jokes she and her fellows play on each other, even during performances. If you've read many of these before, some are still laugh-out-loud funny with her re-telling. These range from trying to eat lunch while dressed as Elizabeth I in Shakespeare in Love to the ongoing transfer of the black glove between her and Tim Pigott-Smith, which started when he, playing Octavius, hid one of his gages in Cleopatra's basket of asps.

Judi Dench is so fond of collegiality, she has never done (and claims she never will do) a one-woman show. And Furthermore is the closest we will get. Like any Dench performance, it is comic and with some heartfelt pathos, warm-hearted and yet intriguing in some unfathomable way. As always, she seems to fully inhabit her character for the audience and gives us a truthful portrayal. Yet, in fact, she really is wearing a mask. What's behind it remains a mystery.

Eric Minton

September 7, 2011

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances Judi Dench: A Great Deal of Laughter

Judi Dench: A Great Deal of Laughter John Miller (Welcome Rain, 2000)

John Miller (Welcome Rain, 2000) Darling Judi: A Celebration of Judi Dench

Darling Judi: A Celebration of Judi Dench Judi Dench (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005)

Judi Dench (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005)