Hamlet…The Rest Is Silence

Visual Soliloquies

Synetic Theater, Arlington, Va.

Sunday, March 16 2014, E-110 (center stalls)

Directed by Paata Tsikurishvili

Though exquisitely performed, Synetic Theater's revival of its production of Hamlet…The Rest Is Silence is most vital in the knowledge of what comes after—not the play but the production itself. This was Synetic's first "wordless Shakespeare" presentation a dozen years ago, and out of this simple but creative production has evolved a Shakespearean genre unto itself generating exciting theater that the Washington, D.C., area can count on year in and year out.

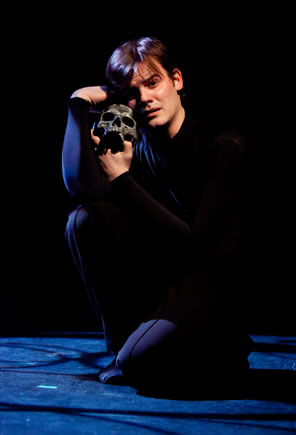

Alex Mills as Hamlet. Photo by Koko Lanham, Synetic Theater.

In 2001, Paata Tsikurishvili and his wife, choreographer Irina Tsikurishvili, natives of the Republic of Georgia, founded Synetic, labeling itself as "movement theater" combining dance, acrobatics, and mime, or what Paata Tsikurishvili calls the "theatrical language of internal expression, psychological gesture, nonrealistic acting, and music." The next year, they set out on an experiment to present William Shakespeare's works without words, and they chose the wordiest of his works, Hamlet, as a start. That selection alone is evidence of their audacity, and the Tsikurishvilis have never been timid, not in his interpreting Shakespeare's language into visual imagery, not in her choreographing Shakespeare's plots into movement.

"Conceptually, our wordless Shakespeare adaptations, and specifically this production, can be most closely associated with that of impressionist painting," Paata Tsikurishvili writes in his program notes for Hamlet…The Rest Is Silence. "The actor's very being becomes the medium, music the paintbrush, the audience both viewer and creator. The result is a living, breathing 'painting.' The image onstage creates a passageway to a new truth, the doorway leading to palpable emotion." If that last sentence seems highfalutin, it is an insight into the Tsikurishvilis and the attitude they bring to their product. Their respect for Shakespeare is channeled through their own artistic egos, and, sometimes frustratingly, you can't have one without the other in Synetic offerings. But without both, you wouldn't get,

- The Tempest danced in an on-stage lake with Ariel costumed like a visual representation of St. Elmo's fire;

- A Midsummer Night's Dream with Puck fishing from the moon, the lovers in an all-out brawl, and the Rude Mechanicals performing hilarious clowning antics to an on-stage piano soundtrack that was more Schroeder with Snoopy than Shakespeare with Burbage;

- Twelfth Night and its silent-movie-era aesthete and dance steps through which the Tsikurishvilis explored the self-reflection theme of the twins in Shakespeare's original;

- The modern Hollywood-set Taming of the Shrew, with its hilariously choreographed banquet (seldom has a feast been so funny, including the Klumps') and its bed trick—not the Measure for Measure kind but the tilting bed that allowed us to see how Petruchio keeps Kate awake all night;

- Romeo and Juliet and the lovers' lovely pas de deux of palms, the presentation of the night before the morning after, and the thrilling fight scenes;

- And four other Silent Shakespeare productions, including acclaimed versions of King Lear and Macbeth, that I have not seen.

It all started with this Hamlet: indeed, the pas de deux of hands performed between Hamlet (Alex Mills) and Ophelia (Irina Kavsadze) in this production was improved and expanded upon when Mills as Romeo performed such a dance with Natalie Berk's Juliet.

This Hamlet comes off exactly as what it is: the first steps of a fledgling company. However, I'm not so sure the Tsikurishvilis would change it much, and they certainly have that opportunity. As Hamlet is more revered for its psychological depth than its plot (killer plot though it is), Synetic's sparse staging and simple choreography is fitting for a play that, as Paata Tsikurishvili says, lends itself so well to engaging the audience's imagination and compelling our involvement in the creative process.

Despite Synetic favorites in the key roles—Mills, Irina Kavsadze, Irina Tsikurishvili as Gertrude, Irakli Kavsadze as Claudius, Scott Brown as Laertes, Philip Fletcher as the Ghost and Player King, Vato Tsikurishvili as Osric and the Gravedigger—the real star of this production is the ensemble: Irina Koval (also the Player Queen), Lorne Britt, Zana Gankhuyag, Randy Snight, Janine Baumgardner, and Emily Whitworth. In black and carrying eight-rung ladders with mirrored rungs, the ensemble becomes both setting and imagery (original set, props, and costume design is by Georgi Alexi-Meskhishvili, who proves that sometimes simple is the bolder way to go).

The ensemble forms the hallways and private rooms of Elsinore, creating arrases behind which eavesdroppers hide. The ensemble forms heaven where Hamlet thinks he will send Claudius if he kills him while praying. The ensemble forms the ship that is meant to take Hamlet to England. The ensemble plays the weeds and the glassy stream, with one dancer as the willow aslant the brook that Ophelia attempts to climb before falling to a drowning death. In one of Irina Tsikurishvili's most clever pieces of choreography, the ensemble becomes the graveyard, forming the earth that moves every time Vato Tsikurishvili's Gravedigger sticks his spade in the ground, out of which Yorick's skull suddenly and surprisingly emerges. The ensemble is even Hamlet's dance partner in his "To be or not to be" soliloquy, presenting the sea of troubles, the whips and scorns of time, and the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveller returns.

Mills is fast becoming one of the Capitol Region's rising stage stars, a solid actor in addition to being a fluidly athletic dancer. However, even in silence, Hamlet puts him to the ultimate test of playing a character. His performance is a restrained one, his expression mostly a blank slate during the soliloquies or, at most, a puzzled look (especially with Yorick). In shared scenes, he plays all his emotions on the surface, which may be merely Hamlet's public persona, but we can't be sure we're seeing anything deeper there. His dance movements, meanwhile, show only hints of his capabilities; I accept that Hamlet is an inward play while Twelfth Night was more broadly presented, but having seen what Mills accomplished as Sebastian, how I wish the Tsikurishvilis had given him the "rogue and peasant slave" soliloquy to perform in this produciton.

As with all his silent Shakespeares, Paata Tsikurishvili makes some interesting choices, some of which are enlightening, some just puzzling. He's good with backstories (whether true to Shakespeare's intents or not), and he presents Hamlet's through the acting out of the Ghost's description of his own murder. In his telling, Gertrude and Claudius were having an affair beforehand. More intriguing, young Hamlet has a friendly relationship with his Uncle Claudius; it is the quick marriage of his mother to her brother-in-law that ignites Hamlet's ire toward the newly crowned king (apparently, this Hamlet has no "prophetic soul"). Polonius (Hector Reynoso) is another matter; he and Hamlet are obviously on the outs from the beginning, but this might be due to the father's protective guard concerning his daughter. In the nunnery scene, as Hamlet physically abuses Ophelia, Polonius attempts to rush out from behind the arras, but Claudius prevents him.

Ophelia (Irina Kavsadze) drowns among her flowers in the stream played by the ensemble in Synetic Theater's production of Hamlet…The Rest Is Silence. Clockwise from upper left, Lorne Britt, Philip Fletcher, Zana Gankhuyag, Randy Snight, Emily Whitworth, and Janine Baumgardner. Photo by Koko Lanham, Synetic Theater.

The Mousetrap ends with some wonderful dramatic and thematic stagecraft. At the point where Claudius would shout, "Give me some light," here the stage lights go down and the ensemble is left on stage holding flashlights shining on the king. He approaches one after another, turns the lights on their faces and, in fear, the dancers scamper away. Soon only one flashlight-holding form is left on stage, and when Claudius turns the light upon him, we see Hamlet staring back at his uncle with a stony "I know you" expression. Only the king's and would-be king's faces are in light; only they know the game (this production dispenses with Horatio). It is therefore a bit strange that Hamlet should act so spirited and carefree in his fencing bout with Laertes, Mills's most animated moment in the play and fun to watch but far removed from the foreboding "about his heart" Hamlet expresses in the play.

Then, the play just ends. An increasingly angry Laertes stabs Hamlet from behind as the latter is communing with his mother, who has just drunk from the poisoned cup. Laertes's overt behavior might seem out of place, but it's part and parcel of "the theatrical language of internal expression." After the catastrophic series of killings, the ensemble enters as Fortinbras's army (though this is the first representation of the Fortinbras plot in the entire production), Mills runs toward the audience and hurls a splattering of blood at a window pane lowered over the stage. The lights go out and only when they come up for the curtain calls does the audience applaud. I'm not sure what, but the audience was expecting more—a closing celebratory all-company dance perhaps? Hamlet and the ensemble teaming up on flights of angels singing him to his rest?

But, in fact, taking in this production's historical perspective, we did get more, so much more. To the Silent Shakespeare that would come over the years, Hamlet…The Rest Is Silence was just the start. And a good start it still is.

Eric Minton

March 20, 2014

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances