End of the Trump Era?

Beyond Shakespeare's Villains

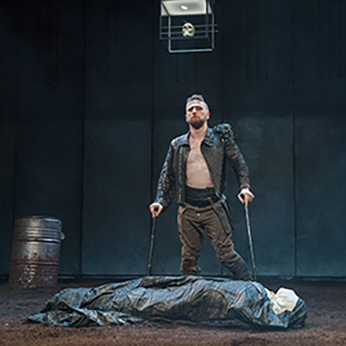

Richard (Aaron Monaghan) stands over the body of Henry VI, wrapped in the train of Lady Anne's dress, in the DruidShakespeare 2019 production of William Shakespeare's Richard III for the Lincoln Center. Photo by Richard Termine, Lincoln Center.

Richard (Aaron Monaghan) stands over the body of Henry VI, wrapped in the train of Lady Anne's dress, in the DruidShakespeare 2019 production of William Shakespeare's Richard III for the Lincoln Center. Photo by Richard Termine, Lincoln Center.The presidency of Donald Trump has been something of a renaissance for William Shakespeare. From the moment of Trump's inauguration four years ago, scholars, commentators, and yours truly have found parallels, if not outright depictions, of the 45th president of the United States in Shakespeare's characters. Villains, mostly. Richard III and Macbeth seem most obvious, but also Julius Caesar, Richard II, Coriolanus, and King Lear. Trump could also be cast as Leontes in A Winter's Tale, Angelo in Measure for Measure, and Iago in Othello. Heck, there's a bit of Trump in Henry VI's Margaret.

DC Metro Theater Arts correspondent and critic Sophia Howes posted a summary article on this topic this past weekend (https://dcmetrotheaterarts.com/2021/01/15/why-trump-has-made-shakespeare-matter-more-than-ever-in-dc/). She argues that "When theater returns at full force on the District's stages, Shakespeare should be our first priority. He is our greatest authority on the use and abuse of power." I say amen! to that, of course.

Yet, these straight-up comparisons between Trump and specific characters have always bothered me. Scholastic discussions, while exploring the various angles of personalities, can trample on the nuanced breadth and depth of the personalities that make Shakespeare's characters so fascinatingly—and sometimes frustratingly—rich. King Lear, for example: The man obviously was an efficient ruler; Shakespeare takes great pains to subtly establish that fact in the opening scene. It's his retirement that he doesn't handle well. While his ego and impetuosity trigger events that ultimately prove fatal to the nation, his offspring are the actual culprits in the kingdom's destruction (Goneril and Regan, Regan's spouse, and the sisters' mutual love interest would then be the more apt comparison of King Lear to the Trump administration).

Commentaries also focus more on the singular characters rather than their contexts, contexts that include not only the other characters on stage but the audience in the seats, too. It's in those roles where I believe Shakespeare's most vital lessons lie as we move forward into the next administration.

Watching the celebratory mood on social media leading up to today's inauguration of Joe Biden as the nation's 46th president, I feel like an extra in Act 5, Scene 5 of Richard III. "The bloody dog is dead" and "we will unite the [blue] rose and the red" and "enrich the time to come with smooth-faced peace, with smiling plenty and fair prosperous days" and "abate the edge of traitors." These are the words of Richmond, who is to become Henry VII. Shakespeare did not continue that monarch's story of consolidating power into a despotic dynasty. If he had, the play would end on the line "What traitor hears me and says not 'Amen'?" spoken with a threatening edge, which is how the upstart crow collective concluded its production at the Seattle Shakespeare Repertory Theatre in 2018.

Shakespeare, though, was not a chronicler. He was a dramatist; let's stick to that realm.

Howes in her DC Metro commentary pointedly desires to see played out in the playhouses Shakespeare's discussion on the use and abuse of power. It is in performance where the nuances emerge, imbued as they are by the talents and experiences of the actors playing them.

Above, Marcus Truschinski as Angelo in American Players Theatre's production of Measure for Measure. Photo by Liz Lauren. Right, George Kozaitis as Prince, CEO of Morroccan Sands Tanning Studio, with Journee Benjamin as Portia in the Children's Shakespeare Theatre's The Merchant of Venice. Photo by Diana Green.

When I accomplished the Shakespeare Canon Project in 2018, seeing all 42 Shakespeare-penned plays at 42 different theaters across the United States and Canada, I saw Trump and his administration reflected in many productions, sometimes boldly, more often subtly, and always evidencing Shakespeare's insight and prescience. These ranged from an outright impersonation of Trump as the Prince of Morocco (owner of a tanning salon) in New York's Children's Shakespeare Theatre production of The Merchant of Venice to Winnipeg's Shakespeare in the Ruins turning Alcibiades into a female, Trump-like real estate investor in Timon of Athens. Wisconsin's American Players Theatre modern-dress production of Measure for Measure echoed many of the the sound bites of the day—literally. "Truth is truth to th'end of reck'ning," I heard Isabella say on stage on the production's opening night. "Truth isn't truth," I heard Rudy Giuliani say on television the next morning.

I also saw Trump in the character of the Bastard in King John at the Texas Shakespeare Festival in Kilgore. Conor Finnerty-Esmonde did not play Phillip the Bastard with any Trump tropes (the setting was medieval), but after six months of seeing the president through so many of Shakespeare's petulant tyrants, I couldn't help seeing the plain-speaking, trash-talking, customs-bashing, überpatriot through the eyes of the Trump-supporting patrons around me. On my visit to the Chicago Shakespeare Theater, I met with Founding Artistic Director Barbara Gaines, who described depicting Jack Cade as Trump in her 2016 Tug of War adaptation of Shakespeare's Henry VI plays. This was before that year's election, she said. And it was funny.

The Cade Rebellion scenes in Henry VI, Part 2, with their anti-intellectualism fervor and xenophobic jokes, is one of the earliest examples of Shakespeare's incisive comical characterizations and wit. One of Shakespeare's most quoted lines comes from a guy named Dick, one of Cade's rebels: "The first thing we do, let's kill all the lawyers." If that line is on the coffee mug you're drinking from, think now about the 2016 terrorist attack in Pakistan that specifically targeted a gathering of lawyers, who comprised most of the 70 people killed and 130 injured. The burgeoning anti-science and xenophobic sentiments in Europe and the United States have further drained the Cade scenes of their humor. Two weeks ago, we saw a real-life Cade Rebellion incited by Trump play out at our nation's Capitol. It wasn't funny.

You know who else in Shakespeare's canon we laugh at? Richard of Gloucester, later Richard III. "What I find really fascinating about [Richard III] is that we're cheering him on because it's entertainment until he's not entertainment anymore," Aaron Monaghan told me in an interview. He played the titular Richard in the 2019 DruidShakespeare production of the play, and when it ran in New York that November, Monaghan had the audience in stitches, until late in the play when his cruelty wasn't funny anymore. The most memorable Richard I've ever seen was Benjamin Curns' performance at the American Shakespeare Center's Blackfriars Playhouse, where audience members sit on "gallants' stools" lining each side of the stage. In my interview with him and Sarah Fallon, who played Queen Margaret, Curns described a performance in which three guys sitting on the stools cheered Richard through two-thirds of the play, until the king tries to talk Elizabeth into marrying her daughter to him. Curns ended the scene with a violent kiss, "and these three guys sitting on the stools go 'Oh!' They shook their heads and looked down at the ground and wouldn't even look at me anymore," he said.

"We get the audience complicit in clapping for him and, 'Yeah, take the throne!" Fallon said. "Then by the end of it, they're just disgusted. But they're all complicit."

If we, the audience, are complicit, what chance do the characters on stage have, people who have an actual stake in how the plot turns out? None of us—hopefully—see ourselves as Richard. How different are we, however, from Buckingham, Hastings, Clarence, Catesby, Elizabeth, and Derby? These people see power, riches, or maybe just security at the end of the line, not their own or their family's destruction. We could even play match the Richard III character to the Trump White House, but I don't want to because I previously met, and still admire, one of the players in Trump's administration. I also have friends and work with people who voted for Trump. Economic self-interest were their sole motivation, not race, social policies, or personality. I saw one poll in which the demographic that overwhelmingly supported Trump was specifically my socioeconomic demographic in race, gender, and income-level. Thus, we must remember that Richard couldn't actually ascend the throne without winning over the Lord Mayor and the people of London.

First, Richard had to get rid of Lord Hastings. With Buckingham's assistance, Richard concocted a lie that Queen Elizabeth and Hasting's mistress used witchcraft to wither his arm. Richard was born with the disability; duh! Yet, none of the other lords raised that point at the time. Upon Hastings' beheading, Richard then delegitimized the young (and soon to be murdered) King Edward V's claim to the crown by convincing the population that the prince was actually a bastard, Richard calling his own mother's fidelity into question. Again, Shakespeare wasn't being an accurate chronicler here: the real Richard III used a sounder legal argument of bastardy (that Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth wasn't legal) to uncrown Edward V. Given what we've been through the past two months, both history's and Shakespeare's versions seem totally in tune with our times, but Shakespeare's is more entertaining.

Jack Cade (Dan Crane, left) fires up his base as he leads a peasant rebellion against the noble class of the realm in Taffety Punk's 2017 Bootleg Shakespeare production of William Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 2, at the Folger Theatre. Photo by Brittany Diliberto, Taffety Punk Theatre Company.

This is the contextual matter that is so important in Shakespeare's presentation of use and abuse of power. Look beyond his portrayal of individuals to his depiction of the whole society—including the audience for whom he was writing, then and now. In this aspect of his work are Shakespeare's lesson concerning our own role in the engendering and rise of tyranny, our self-serving complicity that ultimately turns self-destructive. I suspect the hope so many harbor for today's epoch-changing inauguration isn't taking this context into consideration.

It is why we need Shakespeare's mirror, even before the playhouses reopen, to show us what we really are—how we laugh, until it isn't funny anymore.

Eric Minton

January 20, 2021

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom