Time's Passages

My Love's Labor Now My Winter's Tale

My wife grew old this week. It happened in seconds, about the time it takes William Shakespeare to span 16 years in The Winter's Tale. The day it happened, in fact, was a very Winter's Tale kind of day for me.

I had been pondering posting something this month about our current condition: where we are relative to Sarah's medical issues, my Shakespeare Canon Project (42 Plays, 42 Theaters, One Year), and the lifestyle consequences of both (i.e., dwindling finances). I left off that narrative back in December with Sarah in a perpetual state of debilitating medical mystery and me in a perpetuating state of overwhelm. Since then we've been trying to get answers for Sarah while I've been trying to turn around our declining finances and move forward with the Canon Project book, Where There's a Will: Shakespeareances through the American Way. Meantime, we keep Shakespeareancing. I resisted posting updates on our situation because everything has been in flux, and I just didn't see any real Shakespearean relevance.

Shakespeare, though, has a way of sledgehammering us with his relevance. That happened this week as I slid from Love's Labour's Lost to The Winter's Tale, literally (finishing a review of the former and readying to write reviews on the latter) and figuratively, experiencing an inexorable slide away from the songs of Apollo on the wings of Time.

Tuesday was my Winter's Tale day. Not because it was wintery or Bohemian. Not because I thought Sarah was having an affair with my best friend but she really wasn't. Not because I received an oracle from Apollo or was pursued by a bear or a statue moved. Those elements are in The Winter's Tale, but what I experienced was parallel to the play's construct as a whole, a play with which Shakespeare poignantly portrays lifetime.

Many people, avid Shakesgeeks included, deride the play as too improbable, too disjointed, too unworkable to successfully stage, not just because of its fantastical elements but because it doesn't seem to know what it's supposed to be. From scene to scene—sometimes line to line—the play alternates between disturbing tragedy and sweet comedy. Plot turns come in seven words or less. Leontes, the king of Sicily, grows jealous of his wife, Hermione, who is “too hot, too hot” with his best friend, Polixenes, the king of Bohemia. Leontes' son dies the instant Leontes defies Apollo's creed as “this is mere falsehood.” Immediately after that, “This news is mortal to the queen,” and she dies—sort of. Their daughter is abandoned on the coast of Bohemia (a landlocked country, by the way) by Antigonus, who “exits pursued by a bear.” Sixteen years pass in the time it takes Time to say, “I slide o'er sixteen years.” Then, in a string of fateful circumstances, the daughter, found and raised by an old shepherd, meets Polixenes' son, the couple flees his father's tyranny, everybody ends up back in Sicily proving true Apollo's oracle, and a statue of Hermione comes to life.

I've seen many directors try to disentangle the play from itself by cutting major elements, rearranging scenes, transfering its substance to a conceptual universe, or turning it into a treatise on theatrical imagination. But it's not imagination that you need to appreciate the play. Nor is it a mystery that the productions of The Winter's Tale that prove most comprehensible, enjoyable, and “workable” are those that present it with textual fealty, keeping the order of scenes intact and trimming only a bit of fat but none of its substance.

All you need to make sense of the play is the experience of living. The Winter's Tale plays like life, a tragicomical roller coaster of highs, falls, loops, helixes, thrilling air time, and gut-churning vortexes. To make the play workable, directors need only follow Paulina's instruction when she brings Hermione's statue to life: “It is required you do awake your faith.”

Faith is the one constant psychological attribute that gets us through each and every day, whether that faith is religious in foundation or basic survival instincts.

Such was my Tuesday. I woke up in a bed I'd never slept in before in a place of refuge in a situation of uncertainty. The bed is in the home of Tom Delise, founding artistic director of the Baltimore Shakespeare Factory. He and his wife, Christine, are letting me crash in their spare bedroom this week. I walked the few blocks from their home to the subway station, and while waiting for the train I checked emails on my iPhone. Top of the queue, just arrived, was a message leading off with the line, “Congratulations! I am happy to inform you that all pre-employment conditions have been met and I am extending to you a firm job offer for the position of EDITOR…” (capitalization in original). This is not scam spam. I've been hired as editor for the National Commission on Military Aviation Safety, a bipartisan panel of subject-matter experts selected by Congress and the president to study a recent spate of aviation accidents and make recommendations for legislative and policy changes. This is my third appointment as editor of a national commission in the past seven years, a timeframe that spans my time doing Shakespeareances.com. This recent career track grew out of my previous career as a journalist covering the U.S. armed forces.

This news gladdens and grates. It heralds, finally, income security through at least a year and the chance for financial recovery (Sarah has not been able to work since last June, so we've been making do with her retirement pay and my scant freelance income). This is good news, certainly, but I was tapped for this job back in January. I've waited five months for “all pre-employment conditions” to be met, outlasting a government shutdown, funding hang-ups, and a bureaucracy that makes the Rome of Titus Andronicus look like a model of modern efficiency. My paperwork was finally approved seven weeks ago, yet it stalled out on some desk somwhere. Meantime, our financial hole deepened and the commission's mission was delayed: a year to do our work is now seven months. So my new future is at hand, balancing a high-stress, full-time editing job with finishing Where There's a Will, maintaining Shakespeareances.com., and…

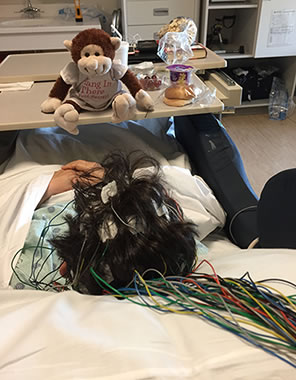

I exited the subway at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, took the elevator to the top of the 12-story Zayed Tower, paused at the locked double doors of the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit until I could be buzzed in, and headed to room 55. This is where Sarah is spending this week. We checked her in Monday, and after a quick introduction to the process and protocols, she had 50-some electrodes glued to her head and attached to an electroencephalograph (EEG). The wires trail off the back of her head, giving her a multicolor, Dutch-braid pony tail (one of the nurses calls it Medusa hair). She's under constant surveillance (cameras follow her around the room), and she can't even go to the bathroom without notifying the nurses and technicians in the “control room.”

Monkey keeps a close eye on Sarah, who is wired to an EEG in her room at Johns Hopkins Hospital's Epilepsy Monitoring Unit in Baltimore. Sarah is enduring seven days of testing and observation, looking for answers to the neurological disorder that has hampered her for more than a year. Photo by Eric Minton.

When I entered her room Tuesday, Sarah was alert and in good spirits. Damn it! It's quite the conundrum to achingly want your wife to get sick. Headache, nausea, dizziness, mental stupor: these are the things she has been suffering for more than a year, identifying onset of intellectual seizures. We want Sarah to suffer all that now so the doctors can identify the source. She has to press a button alerting the technicians whenever she feels any of those symptoms coming on so the doctors can compare the EEG readings with her timeframes of distress. Sarah, though, is stubborn. She tries to get past these moments until I notice the lost, unfocused look that occupies her visage and ask, “Are you OK?” I've become so good at recognizing these onsets before she does that I've considered hiring myself out as a seizure alert dog. That's my primary task through next Monday: to make sure she pushes the button. As Tuesday progressed and they started weening her off her seizure medications, she did, indeed, start having “slight” headaches and “some” nausea, and I made her push the button each time. She never once did it without my prompting, one time even saying about a nauseous spell, "I'm going to see which way it goes." No, push the button! However, I've not seen that lost look when I know a spell is imminent, and the doctors don't see much on the EEG. She's gotten miserable, but we've gotten no wiser.

None of which had anything to do with the real slam to my psyche Tuesday. That moment came as she was eating breakfast. Sitting by her, watching her, I noticed the way she intently studied her food as she picked around it with her fork, the way she chewed with industrious effort, the weariness of her countenance, the frailty of her body. I saw my grandparents there; I saw my parents in their late years. When Sarah turned 60, she was one of the hottest, most active women on the planet; when she turned 61 last November, she had dwindled 25 pounds, and the toll on her aspect was becoming more pronounced, but I still saw her as young, albeit sick. The moment of demarcation between her youth and seniority came Tuesday at the speed of Shakespeare time. I recently experienced the same kind of perceptual transition with one of my brothers. Last September he was my brother; next time I saw him earlier this month, he looked just like our grandfather.

This isn't just about seeing Sarah or my brother as looking significantly older than when I last saw them, though Leontes has a similar moment in The Winter's Tale. When, studying the statue, he notes that Hermione “was not so much wrinkled, nothing so aged as this seems.” This really is a reflection on my own relentless aging (I passed 61 myself earlier this month). It lines up with other such demarcation moments: when my friends' babies graduate from high school, when baseball players we saw climbing the minor leagues enter Major League Baseball's Hall of Fame, when a professional Shakespeare theater casts my son to play Julius Caesar and not Lucius. Times past passed fast.

What scholars label the romances that Shakespeare wrote at the end of his career—Pericles, Cymbeline, The Winter's Tale, The Tempest—have a lot of common themes: family ties lost and found; choices and behaviors leading to disaster, great grief, and psychological distress followed by forgiveness and redemption; significant sea voyages; visits from a god or two; magic or other mystical elements; faith rewarded. They also have another commonality: significant leaps in time. Fourteen years after Pericles leaves his daughter Marina in Tarsus she's kidnapped, and Pericles has 14 years' worth of beard before he finally reunites with her, (apparently adding up to 28 years separation, though it's fuzzy math). Cymbeline's sons were kidnapped “some 20 years” ago. Prospero and Miranda were deposed from Milan and cast away on the island “12 years since” in The Tempest. The Winter's Tale narrative leaps 16 years.

Shakespeare was nearing 50 when he wrote these plays, the latter end of middle age for his time (he was 52 when he died). The special qualities Shakespeare had as a playwright, beyond his brilliant use of words and imagery, were his powers of observation, perception, and empathy with which he captured and explored many elements of the human condition. In these final plays, he seems to be grappling with the most universal of human conditions: a life lived, time lost. The highs and lows, the travels and travails, the successes and defeats, the really, really stupid things done and the miracles of redemption, love won, lost, and found again, and, most significantly, time's passages. What once seemed endless to the mind has, in the final turn, become fleeting. On Tuesday, Time appeared on my stage in the form of my wife laboring through her breakfast. “Now take upon me, in the name of Time, to use my wings,” the moment said, quoting The Winter's Tale. “Impute it not a crime to me or my swift passage, that I slide o'er sixteen years and leave the growth untried of that wide gap, since it is in my power to o'erthrow law and in one self-born hour to plant and o'erwhelm custom.”

Tuesday did have a happy ending. When I left Sarah about 5 p.m. she was feeling far worse than when I arrived in the morning, so I was hopeful of her having a “good” night, diagnostically speaking. That evening, Delise and other members of the Baltimore Shakespeare Factory took me to Camden Yards for an Orioles baseball game. The Orioles got hammered by the New York Yankees, but the fellowship of good company is the greater takeaway.

A day of a life: a merry or sad tale shall it be? Both. As the week progresses, the testing continues, some diagnosis is emerging, and coming into crystalline focus is a line from the play I just reviewed, one of Shakespeare's early comedies, Lover's Labour's Lost: “The words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo.” Don Armado delivers that benediction after that play's comic hijinks are displaced by the intrusion of an out-of-nowhere tragedy. That is the current state of Sarah and me as I am watching our past slide irrevocably further into the past. Don Armado's imagery is most apt. Apollo, the god of arts, health, the sun, and light gives way to Mercury, the winged messenger god and a thief. He's stealing time.

Eric Minton

May 24, 2019

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances