A Tournament of Shakespeareances

The Final Four: A Dream End for a Cinderella

For a tournament overview, click here

For the tournament play-in matches, click here

For results of the First Round matches, click here

For results of the Sweet 16 matches, click here

For results of the Elite Eight matches, click here

We've reached the Final Four of the Tournament of Shakespeareances, and none of it has been premeditated. Do you really think I planned to put Cymbeline in the Final Four? I like the play, but I did not expect such a Cinderella run from it. Even Hamlet sticking around surprises me. I signaled from the outset that Hamlet was not an automatic entry in the Final Four, which was as much to say I was not predicting it to survive the Tragedy Genre bracket—yet, here it is, in the Final Four.

Cymbeline and Hamlet, along with A Midsummer Night's Dream and Richard III, are still dancing because I approached each match-up in each round with nothing less than dedication to this tournament's standard: to judge plays according to the collective performances I've seen. I've had fun, but I've not been frivolous. In fact, The Tempest toppling Twelfth Night was a true surprise. On my brackets chart I had already placed Twelfth Night in the Sweet 16 before I wrote the match summary, but as I was writing I realized I couldn't defend my choice while The Tempest was proving worthier. From that point on I never decided on a winner before writing the summary. That is why Titus Andronicus nearly beat Romeo and Juliet. That is why King Lear defeated Othello and Cymbeline beat The Merchant of Venice literally as I was writing the last sentences of those contests.

For the tournament's semifinals, all plays put up their best five productions and strongest contributors off the bench. I haven't written them yet, so I can't be sure who will be in the title match of titles, but I predict we're going to see one blow-out and one really tight tilt below. So, here goes.

A Midsummer Night's Dream (28) vs. Cymbeline (6)

The tournament's top seed, A Midsummer Night's Dream blew past All's Well That Ends Well, Much Ado About Nothing, and The Comedy of Errors to reach the Final Four as the Comedy Genre representative. Cymbeline emerged from the Tragical-Comical-Historical-Pastoral bracket (nicknamed the Polonius Genre), a sixth seed in the weakest bracket, by squeezing past Measure for Measure and Timon of Athens before toppling Merchant at the buzzer.

Ben Steinfeld as Iachimo and Jessie Austrian as Imogen in the Fiasco Theater production of Cymbeline. Photo by Ari Mintz, Fiasco Theater.

Cymbeline has ridden the 2014 MVP performance of Fiasco's production, which took New York by storm three years ago and which we saw at the Folger Theatre last year. The rest of this play's first five is strong, too: the American Shakespeare Center's (ASC) funny text-centric production in 2012; National Theatre's End Games Festival production in 1988 directed by Peter Hall and featuring Geraldine James as Imogen, Tim Pigott-Smith as Iachimo, and Tony Church as Cymbeline; Shakespeare Theatre Company's 2011 fairy-tale-for-a-child rendition; and Judi Dench as Imogen at the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) in 1979, a production that also featured Ben Kingsley as Iachimo, Roger Rees as Posthumus, Bob Peck as Cloten, Jeffery Dench as Cymbeline, and Timothy Spall as a lord. Beyond those five, I've seen a forgettable production at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival (I truly don't remember anything about it at all). That's all the Cymbelines we've got.

Alex Mills as Puck in Synetic Theater's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream.. Photo by Johnny Shryock, Synetic Theater.

A Midsummer Night's Dream comes into this match with 28 productions to choose from, and we need only five, starting with the Atlanta Shakespeare Tavern's 1997 production, the number-two entry on my Top 40 Shakespeareances list, which got outstanding performances in all three threads of the play: the Athenian lovers, the Rude Mechanicals, and the fairies. The Rude Mechanicals and Titania's fairy train were played by professional dancers, who could bumble as beautifully as they could ballet. Another production that fired on all cylinders was Synetic Theater's 2013 Silent Shakespeare production, with an erotic Oberon and Titania, a puppy-like Puck, catfighting Athenian lovers, and Rude Mechanicals that came to life out of a silent film comedy, complete with on-stage piano soundtrack. My son, Jonathan, played Theseus and Oberon (the latter on stilts) in the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey's school touring production, a Seussian Shakespearean treat (he also played Demetrius in a 2013 Millbrook Playhouse version opposite Madeline Wise as Helena, the best portrayal of that couple I've yet seen). The Bristol Old Vic/Handspring Puppet Company production in 2014 used giant masks for Oberon and Titania, garden tools for Puck, and Bottom's bottom for Bottom as an ass. Rounding out the top five is the Shakespeare Forum's 2012 production, which turned hate into love in the Athenian woods and had me in tears with the Rude Mechanicals' staging of Pyramus and Thisbe. Coming off the bench are other great productions on stage (Shakespeare Theatre Company 2012, Theatre for a New Audience 2013, two at Stratford Festival in 2014), on film (the Still Dreaming documentary last year), on the radio (Lean & Hungry 2011), in a symphony hall (Baltimore Symphony Orchestra 2014), and in a meeting room with one, lone fairy (Tim Crouch's I, Peaseblossom in 2013).

With such representations, A Midsummer Night's Dream runs circles around Cymbeline to advance to the title game.

Hamlet (20) vs. Richard III (14)

The top seed in the History bracket, Richard III held off stiff challenges from its own prequel, Henry VI, Part Three, and its fellow namesake, Richard II, before blowing past Henry V to reach the Final Four. Certainly, it's meeting its headiest competition yet in Hamlet, a consensus favorite (among scholars, anyway) that has proven to be a theatrical juggernaut as it roared through the Tragedy bracket, knocking off Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, and King Lear.

Ethan Sinnott's Richard signs his opening speech as his Shadow (Daniel Corey) interprets in NextStop Theatre's Richard III. Photo by Rebekah Purcell, NextStop Theatre Company.

Richard III is at a disadvantage in total numbers of productions seen, but it has the centerpiece performance of all my memorable Shakespeareances, the ASC 2012 Actors' Renaissance Season production with Benjamin Curns in the title role. Richards also occupy two other Top 20 All-Time Shakespeareances spots: Antony Sher for the RSC in 1985 and Ian McKellen for the National Theatre's touring production in 1992. Only one time have I ever entered a theater and been offered five times the face value for my ticket, and that was for Sher's Richard: catapulting downstage on his crutches, eliciting a collective gasp from the audience. McKellen's, of course, became a movie, though much removed from his exquisite stage portrayal, which included his describing the foregone winter of our discontent while fitting a glove onto his one good hand using just that one good hand. Rounding out the starting lineup are Ethan Sinnott's Deaf Richard at NextStop Theatre last year, and Mark Rylance's Richard in the Shakespeare Globe's original practices production on Broadway in 2013. Despite the stature of this play's title character, Richard III is an ensemble play, and we can look to several well-rounded productions to fill out the bench: in addition to the 2012 ASC and 2013 Globe ensembles, there's the Washington Shakespeare Company's (now WSC Avant Bard) set-in-the-future production in 2010; Brave Spirit's youth-infused production in 2012; Hudson Warehouse's exploration of the various uncles in 2012; and the Drilling Company's modern dress production in a New York City parking lot. While I didn't like Sam Mendes' direction of the play for the Bridge Project in 2012 or Kevin Spacey's portrayal of Richard, it certainly has left a lasting memory (as has a particularly bad portrayal by Derek Jacobi on London's West End in 1989). Such bad Richards at least show the depth Richard III has.

Hamlet (John Skelley), Rosencrantz (Grant Fletcher Prewitt), and Guildenstern (Ian Gould) in The Acting Company's production of Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Photo by Michael Lamont, Guthrie Theater.

Hamlet is the deepest play in the canon—philosophically, at least, and reading the play the first time is on my Top 40 Shakespeareances list at 22. But that doesn't count in this tournament, which is focused on performances of the play, and the highest ranked performance of Hamlet on that list comes in at 27—my then 5-year-old-son Ian pretending to be Hamlet in a neighborhood playground. While Ian was a good Hamlet for his age, he wasn't a great Hamlet for the ages, but the fact that an American Players Theatre production that year (1994) made that much of an impression on him is a credit to the play's stage power. When it comes to indelible productions of Hamlet for me, I can't narrow it down to five. So here are seven: Derek Jacobi's Hamlet for the BBC/Time-Life series in 1980; the 2011 ASC production with John Harrell as Hamlet (Sarah's favorite Shakespeare production of that year); ASC's touring production this year with Patrick Earl as Hamlet; the Shakespeare's Globe touring production in 2012 with Michael Benz as Hamlet; Kenneth Branagh's cinematic production in 1996; Shakespeare Forum's 2012 production with Tyler Moss as Hamlet and Andrus Nichols as Gertrude; and Bedlam's four-actor production in 2013, with director Eric Tucker playing Hamlet and Andrus Nichols playing Gertrude and Ophelia. The next tier are all in some way adaptations: the one-woman Hamlet by Kate Eastwood Norris at the Folger in 2010 (number 37 on my Top 40 Shakespeareances); the one-man Hamlet by Ted van Griethuysen at the Shakespeare Theatre Company last year; the one-man Iranian adaptation Hamlet: the Prince of Grief by Mohammad Charmshir at the Public Theater in 2013; Kimberly Gilbert's Enter Ophelia, distracted for Taffety Punk last year; Faction of Fool's commedia dell'arte take on Hamlecchino in 2012; and Synetic's Silent Shakespeare version in 2014. To this list I'll add the Acting Company's touring repertory of Hamlet and Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, in which the latter informed the former and remains the more poignant memory. This presents us with a dilemma: Should these productions be given lesser weight for not really being Hamlet, or should they give Hamlet greater weight in this competition for demonstrating the depth and breadth of this play?

For the purposes of this tournament (and the fact that Romeo and Juliet got past Titus Andronicus in the first round on the basis of its adaptations), the variants are part of Hamlet's stage heritage and ongoing stage presence. That Shakespeare's play inspired a modern classic in Stoppard's play is evidence of Hamlet's power on the imagination. Richard III has the big III Richards in Curns, Sher, and McKellen; but Hamlet and all its little Hamlets just keep coming and coming, and, therefore, continue on to the Tournament of Shakespeareances final against A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Tomorrow, we crown a champion: the king and queen of the fairies or the prince of Denmark.

Eric Minton

April 6, 2015

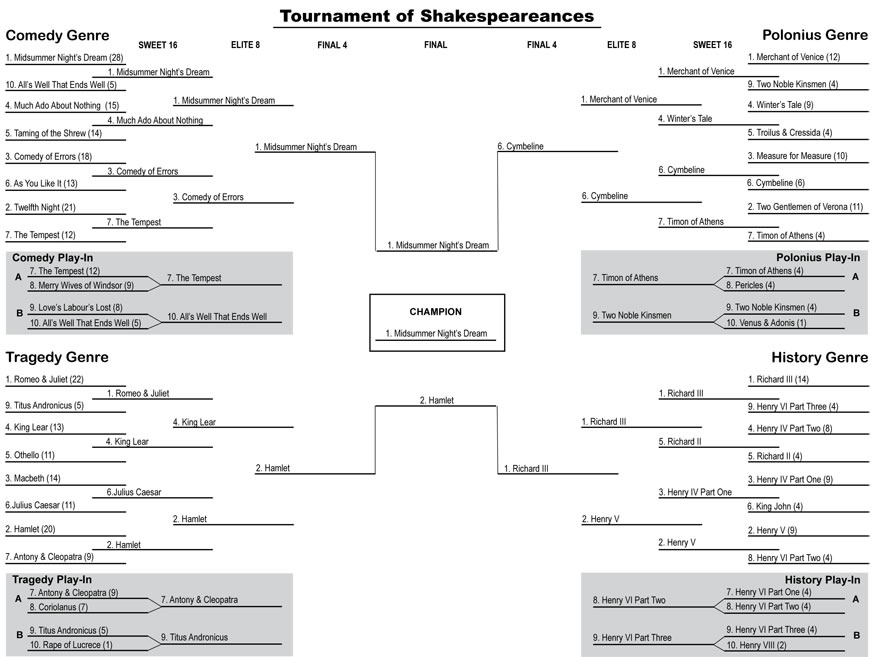

The Brackets

Click on the tournament brackets below to download a PDF version. The play titles on the PDF version are linked to their individual "Productions Seen" page on Shakespeareances.com.

For a tournament overview, click here

For the tournament play-in matches, click here

For results of the First Round matches, click here

For results of the Sweet 16 matches, click here

For results of the Elite Eight matches, click here

For the result of the title match, click here

Comment: e-mail editorial@shakespeareances.com

Start a discussion in the Bardroom

Find additional Shakespeareances

Find additional Shakespeareances